CITY WATCH

Council agenda: The Boca Raton City Council’s annual goal-setting session this week may sound a lot like last year’s. But based on interviews with the five council members, two issues seem as if they will be priorities for the next 12 months. If so, they will be excellent priorities.

On Thursday and Friday at the municipal complex in northwest Boca, some council members will note that one of last year’s priorities—development of the city-owned former Wildflower restaurant property—remains unmet. But the city does have a tenant willing to build a Houston’s restaurant on the site if parking issues can be resolved. So any added action by the council will have to wait.

Regarding another item from last year’s session, the city and Florida Atlantic University are nearing agreement on a new zoning plan for what Boca Raton is calling the 20th Street Corridor. It would create a spiffier eastern entrance to the university and a student-friendly neighborhood in what now is a hodgepodge of businesses. I will have more on that soon.

On issues that affect the whole city, however, expect to hear a lot this week about permitting and pensions.

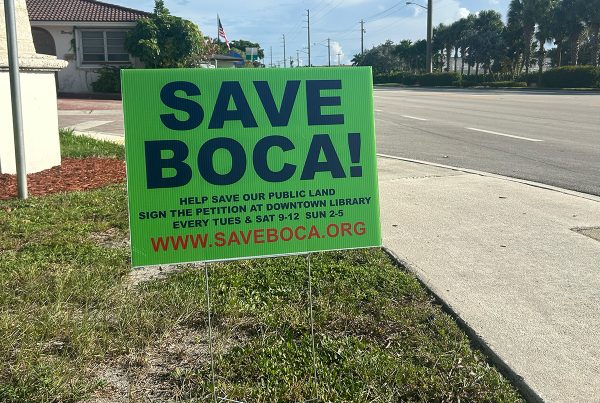

From contractors to business owners to homeowners just trying to remodel a bathroom, almost everyone in Boca has a gripe about how long it takes to get a permit from the Development Services Department. New council member Robert Weinroth cited a church day-care center that had “the proper zoning and no issues” but still had to wait nine months. Mayor Susan Haynie said just swapping out an air-conditioning unit can take 21 days. (As evidenced by the photo below, permitting assistance has become a cottage industry.)

Council members Constance Scott and Scott Singer also cited problems in Development Services. Scott said it is one of the “internal issues” she wants to address. “It starts with leadership,” she said, “and it’s part management, culture and organization.” Singer wants to improve “the customer-service experience at all levels of city government,” including “easing the burdens and the delays associated with a variety of permits and applications and increasing their availability online.” The council should make City Manager Leif Ahnell—on the job for 15 years—responsible for that culture and managerial change.

When it comes to pensions, however, the responsibility rests more with the council, because pension benefits is a policy issue. Mike Mullaugh called police and fire pension reform one of the unmet goals from last year, but since then former council member Anthony Majhess—a Palm Beach County firefighter who had strong backing from the public safety unions—lost convincingly to Haynie in a bid for mayor. Momentum is on the side of reform.

At less than $4 for every $1,000 of assessed value, Boca Raton’s tax rate is among the lowest of any Palm Beach County city. But fire and police pensions still represent the greatest threat to Boca Raton’s long-term financial stability. The same is true in Delray Beach, where the tax rate is roughly double that of Boca. Unless benefits decrease, the share from city budgets to pay for those benefits will increase, which could force a city to raise taxes.

The Boca council must address questions such as: Why should retired firefighters get a 3 percent annual cost-of-living increase in their pensions starting at age 52? Most private-sector pensions don’t have cost-of-living increases. And why should police officers get to include as many as 300 hours of overtime pay in their pension benefit calculations? State law allows it, but that doesn’t mean a city has to go along. Steering overtime to officers nearing retirement is one way to rig the system.

The Boca firefighters’ contract comes up for renewal this year. Whatever the council does—or doesn’t do—will set the tone for the police contract. Boca Raton’s public safety pension benefits should follow guidelines for police use of force: reasonable, not excessive.

••••••••

Independence day for the CRA? Under Boca Raton’s goal-setting guidelines, the council members vote on priorities for the coming year. A proposal must get enough votes to make the agenda. One of Weinroth’s ideas may not make it his year, but either way it deserves a good hearing.

Weinroth wants the city to have an independent director of the community redevelopment agency. That was the system until 2008, when Ahnell took over from Jorge Camejo, making Ahnell city manager and CRA director. Only Boca has its manager in that dual role. The mayor and council also serve as the CRA board.

“The business community has been harping on this,” Weinroth said, “because the CRA is really a city within a city, and the director’s job is very labor intensive.” Since none of the council members claims to be happy with the progress of downtown development, it’s at least time to think about once again splitting the role.

••••••••

Sounds of silence: It seems “solid,” according to a Palm Beach County lobbyist, that the 2014-15 state budget will include $10 million for “quiet zones”—safety upgrades at railroad crossings for increased traffic. The upgrades could mean that trains don’t have to blow their whistles as they approach a crossing.

Quiet zones have been an issue in part because of the proposed All Aboard Florida high-speed service between Miami and Orlando. It will add 32 trains a day—16 each way—to freight traffic on the Florida East Coast Railway tracks that go through downtowns in Boca Raton, Delray Beach and many county cities.

Palm Beach County’s Metropolitan Planning Agency already has set aside $6 million for quiet zones. Cities have been seeking enough money to avoid having to pay for the upgrades. The $10 million from the state would help, but Haynie noted Monday that the money could be spent statewide. Communities in Central Florida will want some of it for upgrades related to the new SunRail commuter train service in the Orlando area.

Further, Haynie said in an email, the state money requires matching amounts from cities. And upgrades for the 176 crossings in Palm Beach and Broward counties—Boca Raton has 10 crossings—will cost $40 million. The state money can be “part of our solution,” Haynie said, but the counties will keep pushing for a federal grant.

••••••••

FSU’s Thrasher problem: In January, a politician tried to leverage his office to become president of Florida Atlantic University. Thanks to key members of the search committee, Florida Chief Financial Officer Jeff Atwater is still CFO, and John Kelly is president of FAU. Atwater’s professional experience is in banking, not education.

Now, though, the talk in Tallahassee is that State Sen. John Thrasher might become the next president of Florida State University. Eric Barron resigned from FSU in February to become president of Penn State.

Like Atwater, Thrasher has no professional background in education except when it comes to votes on education issues. Thrasher’s record, though, shows why he would be a terrible choice to run FSU or any other university in Florida.

In 2001, as a member of the Florida House, Thrasher strongly supported of legislation that abolished the Board of Regents, which had overseen higher education, and created separate boards of trustees at Florida’s public universities. (Voters created a new Board of Regents in 2002, but it has much less power.) That change created a free-for-all and led to a dramatic rise in salaries of university presidents.

In 2003, for example, Frank Brogan was hired as FAU’s president and given a base salary that was $100,000 more than Anthony Catanese had made. (Brogan also was the first to live in the $3 million mansion built for FAU’s leader.) Ten years ago, the president of the University of Florida made $350,000 in base salary. Today, the UF president pulls down more than $1 million in total compensation.

And though most observers would consider FSU one of the state’s two most important universities with UF, Barron’s compensation package ranked behind those for the presidents of Central Florida, North Florida and Florida International. That’s just one way in which higher education policy in Florida makes no sense. Another? In 2012, the Legislature and Gov. Rick Scott created a 12th university—Florida Polytechnic in Lakeland—just because the chairman of the Senate Budget Committee was retiring and wanted the project for his hometown.

Money for that university needlessly sucks money from FAU and the others. A big supporter of Florida Polytechnic? John Thrasher.