The “place” in French photographer and curator Frederic Brenner’s exhibition “This Place” is none other than Israel/Palestine, the most contested region on earth—a political football that Brenner correctly summarizes as “a place of dissonance, of human polyphony and radical otherness.”

But the cradle of three world religions is also a (somewhat) functioning nation, where residents pursue everyday goals amid existential threats of bombings, stabbings, intifadas and new settlements. In enlisting 11 fellow photographers from around the world to present Israel through their personal lenses, Brenner’s diverse and illuminating exhibit serves as both objective reportage and subjective comment, offering views of this Middle Eastern flashpoint that span global perspectives.

The exhibition, which is currently enjoying its U.S. premiere at the Norton Museum Art, encompasses everything from Jeff Wall’s “Daybreak”—a single photo of laborers rustling from their slumber under an olive tree—to Wendy Ewald’s hundreds of postcard-sized snapshots taken by students in 14 workshops she orchestrated in Israel and the West Bank. The exhibit opens, appropriately enough, with the Brenner photographs that inspired his worldwide project.

Brenner’s Israel is one of bright colors and high definition, but with a melancholy lingering just under the surfaces, whether it’s a family posing for a shot at a seemingly desolate beach, or nine children slouching and suffering through an Orthodox dinner at a cinematically long kitchen table. His “Palace Hotel” image is anything but a publicity shot of the titular tourist monolith; it looks like an invasive eyesore sprouting incongruously from an otherwise unspoiled desert.

Germany’s Thomas Struth also favors large-scale, full-color landscapes rich in detail—discovering in Israel, according to the wall text, “a geographic container for the scope of the human condition.” Which is ironic, considering humans rarely appear in his depopulated topographies, whose vistas echo Brenner’s depiction of societal encroachment on ancient geology.

Generally, the deeper you explore “This Place,” the wilder and fringier it gets, with seemingly unfiltered landscape photography acquiescing to more pointed political statements. Fazal Sheikh’s “Desert Bloom” series chronicles the transformation of Palestinian land in the Negev Desert into settlements following the 1948 Arab-Israeli War. He accomplishes this through dozens of identically sized square aerial images of the desert marked and crisscrossed with holes, tracks, land plots and helipads, the occasional construction vehicle. In its totality, “Desert Bloom” suggests an abstract alien land gradually and methodically claimed by terrestrials.

This sense of cultural and religious division imbues some of the finest work in “This Place.” Korean artist Jungjin Lee’s “Unnamed Road” series, shot on colorless mulberry paper, is a post-apocalyptic catalog of dread. Her fuzzy, bleak, nocturnal images seem to have the texture of charcoal, an appropriate comparison considering the charred-earth content of her landscapes; one such image could be an empty greenhouse, but under her lens it’s more likely a labor camp.

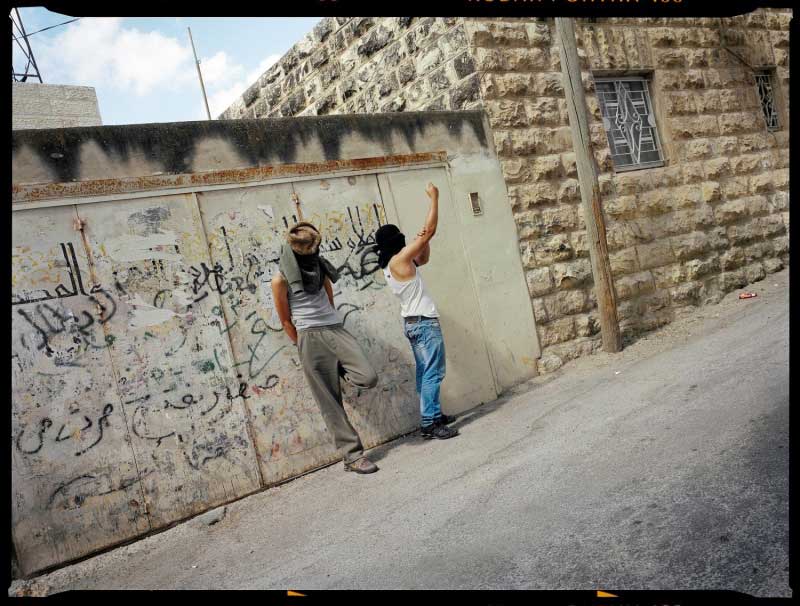

For his part, Gilles Peress focused his time in Israel on the West Bank line, capturing the daily grievances and palpable tensions of so many checkpoints and border towns. It’s hard not to think of our own border with Mexico, an analogy that screams for an even more concrete comparison in Josef Koudelka’s “The Wall”—a collection of shots taken of and around the “security fence” or “apartheid wall” (depending on which side you favor) separating Israel from the Palestinian territories. It forecasts a major plank of Donald Trump’s platform in all its nasty divisiveness.

But other contributors to “This Place” disarm us, breaking down our preconceived political notions. Nick Waplington’s classicist family portraits of Israeli settlers in the West Bank manage to defuse the contempt that many progressives feel toward these obstinate “invaders.” Under Waplington’s lens, they all look like nice people raising innocent children in stable homes. By forcing us to see them as people, Waplington defuses their negative symbolism.

Best of all is Ewald’s veritable rainbow of images, taken by photography students she advised in 14 workshops throughout the region. Some of the snapshots indicate a more embedded militarism than others, but the takeaway is one of universality and connectedness. Jews and Muslims alike chose to photograph family, friends, community, pets, love and beauty. In a region that only tends to make news when bodies are counted and sabers are rattled, Ewald’s project is a hopeful reminder that we’re all one.

“This Place” runs through Jan. 17 at Norton Museum of Art, 1451 S. Olive Ave., West Palm Beach. Admission is $5 adults, $12 adults. Frederic Brenner and Nick Waplington will appear in person at next week’s Art After Dark to discuss their work, at 6:30 p.m. Nov. 19. Call 561/832-5196 or visit norton.org.