For most of you reading this blog, illegal immigration is an abstract issue, a distant concern, a political talking point. For the people drawn by Plantation-based artist Jose Alvarez (D.O.P.A.) in the Boca Museum’s illuminating exhibition “Krome,” being “illegal” is their everyday reality.

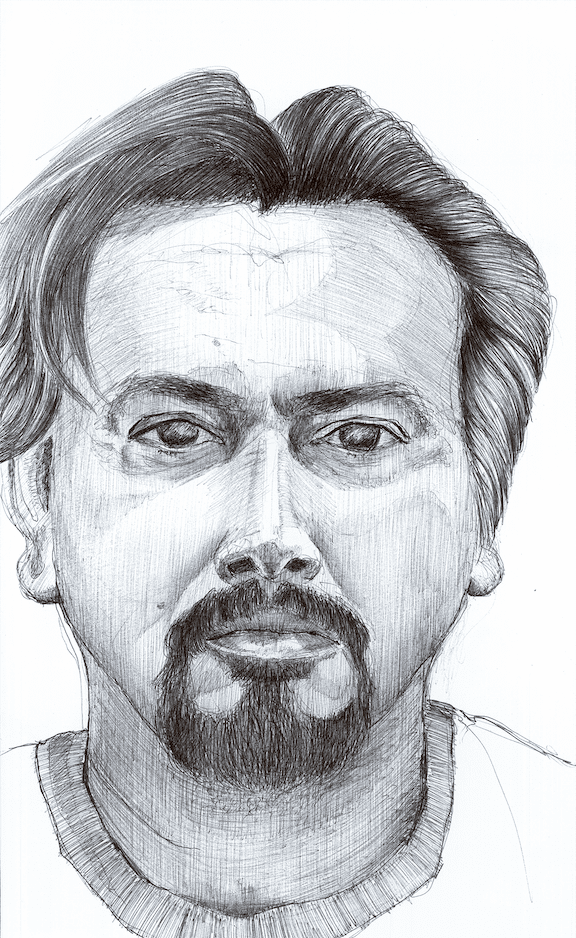

The show draws its title from Dade County’s Krome Detention Center, an isolated penitentiary for individuals with legal-status issues 30 miles west of Miami. Alvarez, whose real name is Devyi Orangel Pena Arteaga (D.O.P.A.), and whose husband is the famed magician and paranormal debunker James Randi, spent two months in Krome in 2012 after he was apprehended on identity theft charges. Rather than sulk in despair, Alvarez continued to practice art from his cell, thanks to a fellow-prisoner’s encouragement. A mug shot-style close-up of that prisoner, a Brazilian named Julio, became the first of more than 30 drawings Alvarez composed of Krome detainees, sketched on whatever scraps of paper were available.

On the day of my visit, Boca Museum Executive Director Irvin Lippman commented that Alvarez’s drawings “humanize a statistic.” Alvarez, who was clearly changed by his experience, arrived at an even loftier conclusion. The drawings were “a way for art to become my salvation and give voices to the voiceless.”

There’s a stark beauty in each of his unadorned drawings, which improve as you move through the small but impactful exhibition, their creator growing increasingly comfortable with the style and limitations of his medium. Completed not with a proper pen but with pen refills—those were the only tools the wardens allowed—Alvarez captured the inmates’ physical intricacies as well as their spiritual energies. The quality of the shading, the bristle of the subjects’ goatees and the wild strands of their hair, the expert curves of their ears and worry lines on their foreheads: All offer unflinching peaks into the souls of the dispossessed.

Alvarez interviewed the majority of the detainees he drew, and their stories of hardship further coarsen the drawings’ rough edges. Orlin, depicted as an elegant man with high cheekbones and a full shock of hair, survived a harrowing ordeal when he escaped gang violence in Guatemala. Adrian fled Colombian extortionists. Patrik was robbed of thousands of dollars by an unscrupulous immigration lawyer, and Jose—drawn as a guru-like figure with leonine locks—trekked eight days in the desert from Mexico to the U.S., surviving on cacti. Roberto Q., a sad-eyed Quetchi Indian, would search barren fields for deflated soccer balls, which he would tear into halves and use for shoes.

Every detainee had a similar story of peril and woe, of escaping a personal hell of crime and destitution through a border crossing no less harrowing, only to find themselves corralled by American authorities weeks or years or decades later—the enervating postscript to a life spent in the shadows. These are not the rapists and killers of which the Republican nominee for president speaks when he rails against the horrors of illegal immigration. These are family men, loyal workers and freedom seekers with eyes full of kindness, compassion and yearning, and “Krome” should be a wakeup call to anyone who sees the mass of immigrants in this country as anything but.

It certainly was for Alvarez, normally a geometrically precise abstract painter of kaleidoscopic shapes and vivid colors. His cosmic, hallucinogenic “Promised Land,” the first piece he completed after his release from Krome, and included this exhibit, is more akin to his usual style. Not only has Alvarez’s time at Krome seemed to expand his empathy for the paperless around us; it also made him into a more diverse artist capable of mastering a style that couldn’t be further from his natural muse. No matter how you view it, it was time well spent.

“Jose Alvarez (D.O.P.A.): Krome” runs through Jan. 8 at Boca Raton Museum of Art. Admission costs $10-$12, or free for children. Call 561/392-2500 or visit bocamuseum.org.