There are few scenes of outright suffering and misery in the illustrations and watercolors of Takuichi Fujii, a first-generation Japanese American living in Seattle who, like 120,000 of his fellow U.S. residents of Japanese descent, spent years interned in a labor camp during the outbreak of World War II. Perhaps that’s because, like many artists in the great realist tradition, Fujii was not prone to hyperbole, and he didn’t use his talent to create agitprop. Righteous anger, it seems, was not his forte, even though it would certainly have been justified.

Judging by the dozens of works, from a recovered collection of some 130 illustrations he completed while imprisoned by the U.S. government, that are on display in the Morikami’s powerful new exhibition “Witness to Wartime,” Fujii saw himself as something of an objective reporter or historian, offering a literary as well as a visual chronicle—the watercolors were found amid a 400-page diary from his time as an incarcerated citizen—from a shameful period in American history.

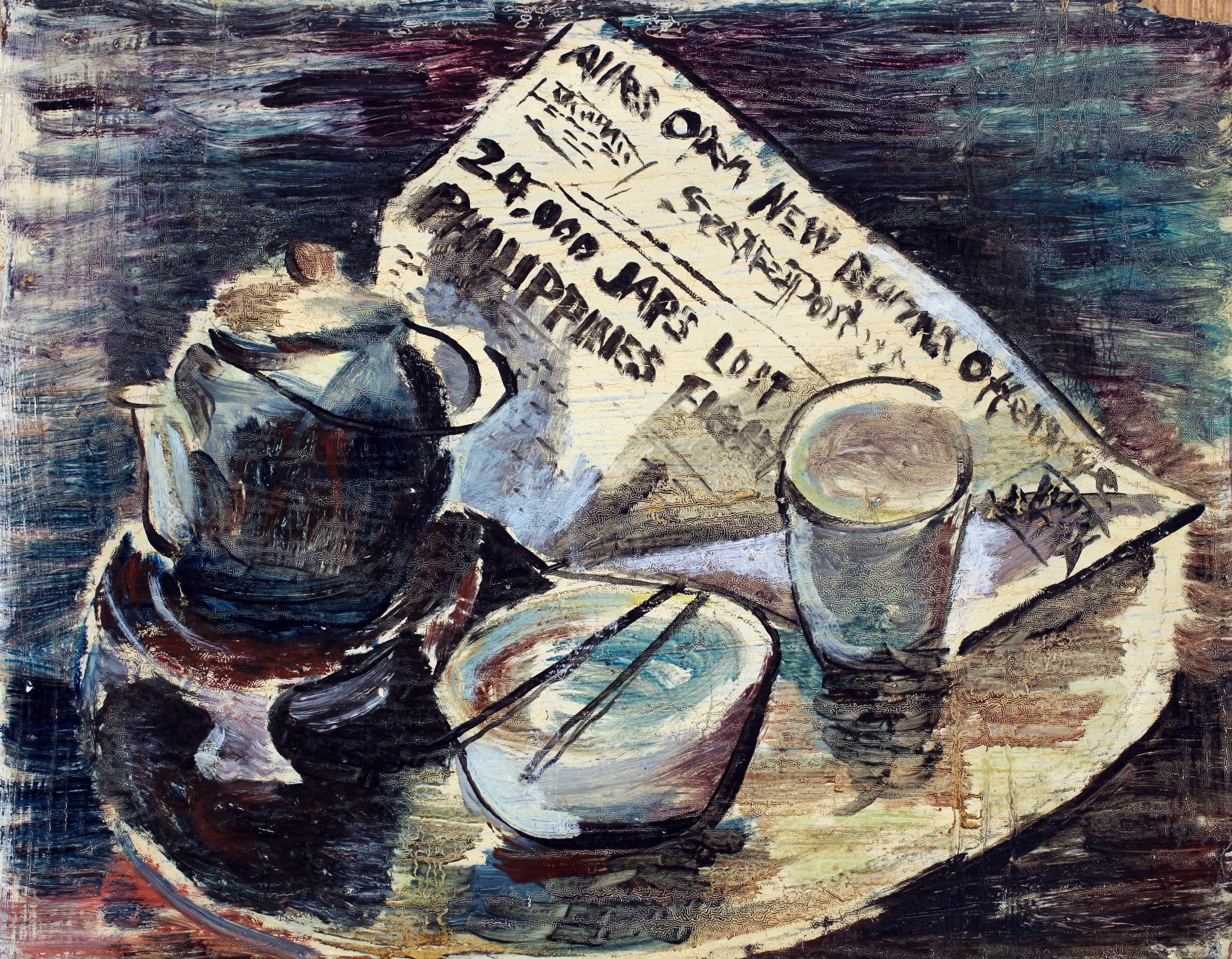

And indeed, it’s the generic blandness that gets to you the most. Completing his scenes on surfaces sometimes no larger than a postcard, the artist (Fujii created plenty of laudable and jury-selected work, in various stylistic traditions, both before and after the war) captured the Payallup Assembly Center (its Orwellian name at the time was “Camp Harmony”) and the Minidoka War Relocation Center from every possible vantage point. He was like a surveyor of the land in all its indistinguishable, utilitarian particulars: dirt pathways, squat buildings, barbwire fencing, laundry hanging on a clothesline. Arms-wielding guards appear in one image, but by and large, this hardly seems the stuff of nightmares. Some of Fujii’s scenes, liberated from their context, could pass for rustic pastorals, like the aptly titled “Feeding the Hogs.” And the medium of watercolor, by its very nature, softens any subject it touches.

All of this seems very much the point of it all: This wasn’t Auschwitz or Dachau but an American form of incarceration camp, where the prisoners can occasionally be seen at rest, or even enjoying themselves in a rice-pounding ceremony. It’s not difficult to conjure some propagandist on some state-media outlet in 1940s America finding enough selective evidence in Fujii’s trove of objective data to whitewash the entire imprisonment of hundreds of thousands of American citizens as a vacation from their normal lives, bought and paid for by Uncle Sam. In some paintings, Fujii shows himself being treated for snakebites and tick-born illness by the medical staff. “Look, America—we even gave them free health care!”

They’d have to ignore, of course, the silent menace percolating just below the surface of Fujii’s watercolors and illustrations, which occasionally bubbles to the top. “Gravestones,” for instance, presents a few of the hastily built headstones for some of the “relocated” who died at the camps.

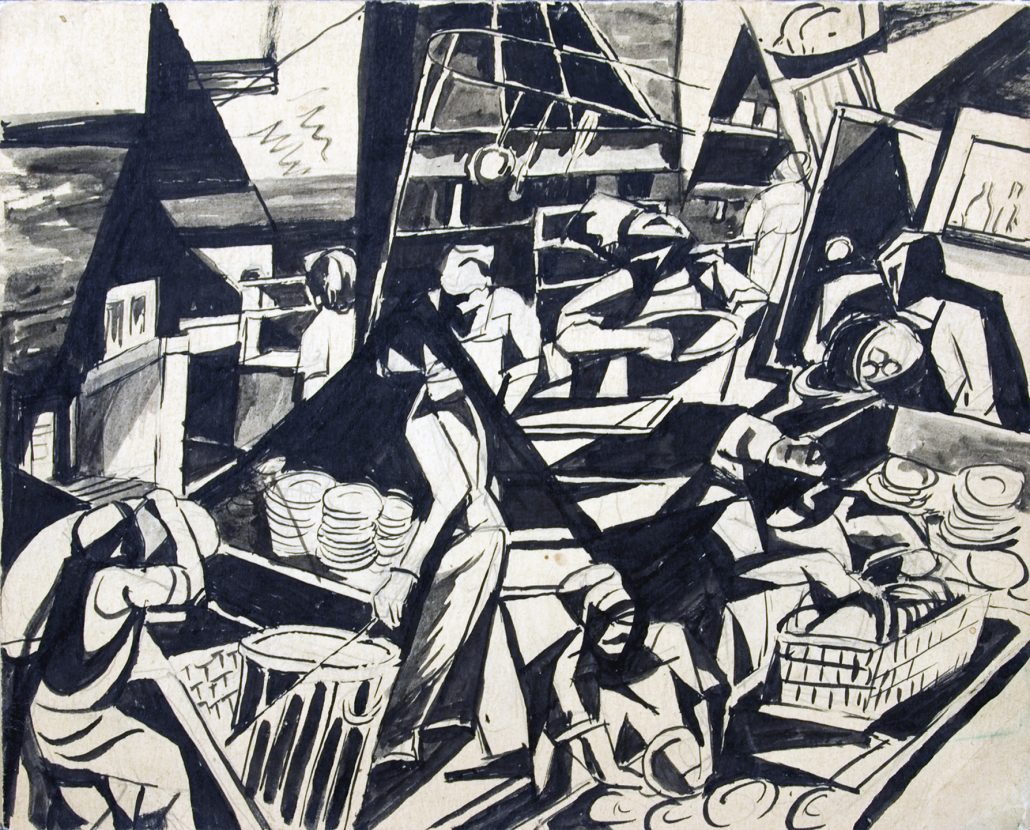

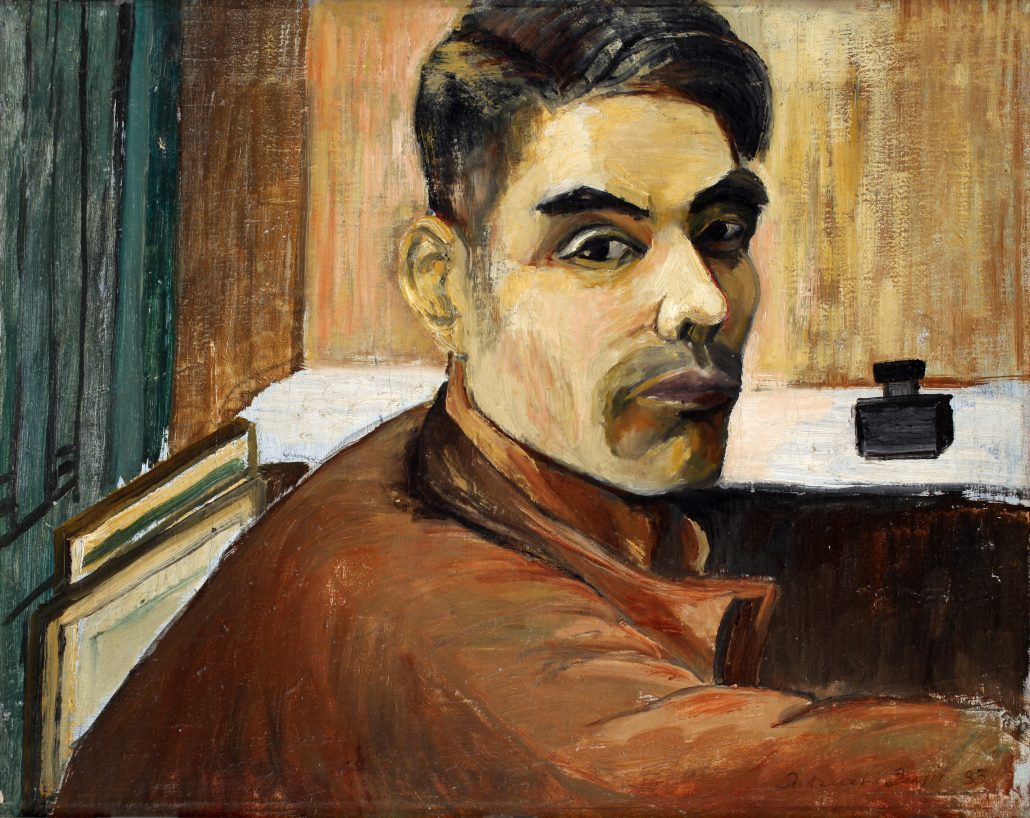

While Fujii outlived the ordeal, “Witness to Wartime” suggests a man forever changed. In a self-portrait he painted prior to his incarceration, his eyebrows arch upward in curious contentment. In a similar painting following his internment, his face appears completely ashen—a haunting image of a haunted figure. Fujii’s work would take an ominous abstract tenor while living in Chicago after the war, almost like Rorschach mysteries in austere black and white, a far cry from his paintings of dams and bridges and people that predated his internment.

There’s a dogged survivalism at the heart of Fujii’s project, and by extension this indispensable exhibition. It’s easy to imagine that, in keeping a historical and visual record of this time of racism and paranoia run amok in the United States, Fujii maintained his sanity as well as his command of line and form and shadow: An artist will always be an artist, even in the most inhospitable conditions. And in the process, he helped show the rest of us that Hannah Arendt’s famous thesis from her reporting on the Adolph Eichmann trial holds in the land of the free as well. “Witness to Wartime” is nothing if not an expression of the banality of evil.

“Witness to Wartime: The Painted Diary of Takuichi Fujii” runs through Oct. 6 at Morikami Museum and Japanese Gardens, 4000 Morikami Park Road, Delray Beach. Admission costs $9 to $15. Call 561/495-0233 or visit morikami.org.

For more of Boca magazine’s arts and entertainment coverage, click here.