All Aboard picking up steam

Throughout Palm Beach County and points north have come calls for “someone” to “stop” All Aboard Florida. But there doesn’t seem to be any “someone” who could “stop” the Miami-Orlando passenger rail project, and there certainly isn’t any consensus that “someone” should.

This week, U.S. Rep. Patrick Murphy, the Democrat who represents northern Palm Beach County and the Treasure Coast, announced that the Coast Guard would hold public hearings to hear comments—meaning complaints—about how the extra 32 trains a day on the Florida East Coast Railway tracks could affect navigation. The first hearing will take place Oct. 2 at the Embassy Suites in Palm Beach Gardens (4350 PGA Blvd., Palm Beach Gardens) and will concern boat traffic on the Loxahatchee River. The next day, a hearing will be held on Hutchinson Island in Martin County, at the Marriott Beach Resort & Marina(555 N.E. Ocean Blvd., Stuart), dealing with boat traffic on the St. Lucie River. They will follow an Oct. 1 hearing about traffic on the New River in Fort Lauderdale.

Opposition to All Aboard Florida increases as you move north from Miami-Dade and Broward counties, where the FEC runs mostly through industrial areas and over few major bridges. Much of the grumbling in the Boca Raton-Delray Beach area concerned noise from horns as the 16 trains per day each day cruise through near residential neighborhoods. Since money from All Aboard Florida and the federal government—channeled through Palm Beach County’s Metropolitan Planning Organization—will pay for “quiet zones” at crossings, some of that grumbling will stop. South of West Palm Beach, horns will sound at crossings, not on the trains, and will be much quieter. The new passenger trains won’t run late at night.

Still, some residents near the tracks complain that they will get just hassles from All Aboard Florida and no benefits, since the only station will be in West Palm Beach. The Delray Beach City Commission held a “discussion” Tuesday night about All Aboard Florida. Some Realtor groups have opposed the project, fearing that it would lower property values of homes near the track. Palm Beach County Property Appraiser Gary Nikolits agreed.

So let’s look at where All Aboard Florida stands and what might happen.

In this story, the main government player is the Federal Railroad Administration (FRA), part of the U.S. Department of Transportation. The FRA must ensure that All Aboard Florida complies with safety regulations and will determine whether the company gets the $1.6 billion federal loan it has requested. The money would come from the Railroad Rehabilitation & Improvement Financing program, created 16 years ago. All Aboard Florida’s would be the largest loan since at least 2002, according to the program’s website. The company would have to put up collateral. In an interview Wednesday, All Aboard Florida President Michael Reininger said the money would pay for “all aspects” of the project, including trains.

The next key moment is release of the FRA’s Environmental Impact Statement for the West Palm-Orlando link. The statement for the West Palm-Miami section found no significant problems, and work on that part of the project—such as building a second track, so trains don’t have to stop—has begun. All Aboard Florida expects to begin service from Miami to West Palm Beach—with a stop in Fort Lauderdale—in 2016, and service from Miami to Orlando—through Cocoa Beach—in 2017.

Reininger said the statement will be one factor in the government’s decision on the loan. If the government does not approve it, Reininger said All Aboard Florida will seek other financing. Release of the statement should come soon, and Reininger expects to know about the loan by Dec. 31.

Technically, the railroad administration reports to President Obama. Opponents, though, should not assume that pressure even from Democrats with much more clout than the first-term like Murphy would cause Obama to break away from matters like the Islamic State, Ukraine and the economy to involve himself in a regional transportation project.

Another big player is the Florida Department of Transportation. Like the FRA, it is an executive agency, but on the state level. Gov. Rick Scott first embraced All Aboard Florida, but then tempered his enthusiasm as local opposition rose. Though Murphy is a Democrat, many of his constituents are Republicans. The district of State Sen. Joe Negron, a Republican, overlaps much of Murphy’s district. Negron also opposes All Aboard Florida.

Like Murphy, Scott is running for reelection. So Scott pushed for the department to set high safety standards, which led in part to the quiet zones. Even if the state were unhappy, though, Scott could not block All Aboard Florida. The company is part of Florida East Coast Industries, which owns the track and the right of way along the track. If All Aboard Florida follows the government’s instructions, the company can do what it wants.

Which brings us to the Coast Guard and the hearings next month, which Murphy requested. Residents will tell the Coast Guard that navigation will suffer because of All Aboard Florida. In Boca Raton, drivers might wait a minute or so for gates to come down and the train to pass. Bridges that usually are open to let boats pass, though, would have to be closed another 32 times a day. Given the age of the bridges and other factors, critics say, Murphy’s office claims that boats could have to wait as long as 30 to 45 minutes, which over the course of the day would mean big navigational problems and a blow to area businesses.

Still, the Coast Guard likely would ask for modifications, not kill the project. A spokeswoman for Rep. Murphy acknowledged that “no agency can stop” All Aboard Florida if the company follows state and federal laws. His office wants people to “speak up and have their concerns heard. . .particularly as it relates to whether or not taxpayer funding is used to support this project.”

If All Aboard Florida seems less of a big deal to Boca Raton and Delray Beach at this point, however, that isn’t necessarily so. Adding that second track could mean more freight trains, as more cargo through the expanded Panama Canal comes to South Florida. But there’s a plan to shift some of those trains in Pompano Beach to the CSX tracks, farther west.

And transportation planners long have hoped for a commuter rail system on the FEC tracks, which run through downtowns, and could be more popular than Tri-Rail, on the CSX. City officials who are hinky about All Aboard Florida love that idea. All Aboard Florida has made no commitment to allowing such a service, but the discussion between Florida East Coast Industries and public agencies will continue.

Critics of All Aboard Florida will have to accept that they can’t stop the project. It also will take several years to determine what All Aboard Florida will mean to South Florida. As Murphy’s spokesman said, citizens can “make AAF address potential harms,” a process that will start when the feds release the second Environmental Impact Statement. All Aboard Florida is leaving the station. The question now is what the ride will be like.

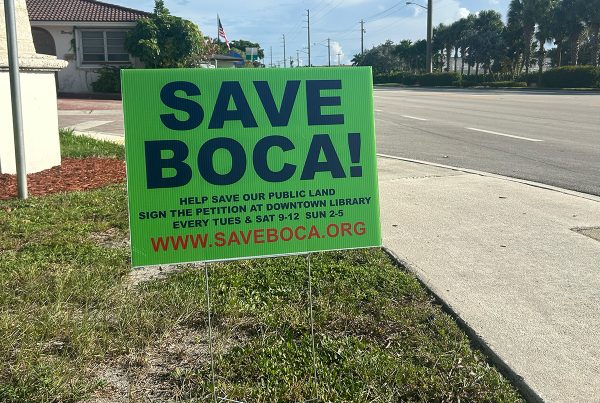

Too big for Boca?

On Tuesday, I wrote about the four-tower New Mizner on the Green luxury condo project proposed for land between Mizner Boulevard and the Boca Raton Resort & Club. (Click here to see the blog). Boca Raton City Councilman Robert Weinroth agrees that New Mizner is a “beautiful project,” with its high-tech design. Weinroth also says, however, that New Mizner is “not for Boca.”

Why not? Height limits, Weinroth said. They are 100 feet on the property itself, 140 feet around the site, and can be stretched to maybe 160 by structures on tops of buildings. New Mizner’s towers, though, would average about 300 feet. “The community,” Weinroth said, “is not ready to embrace it.”

Councilman Mike Mullaugh is less dismissive. Mullaugh says Boca has been “most everything” envisioned when voters in 1993 approved Ordinance 4035, which generally set the terms for downtown development. He says the city is entering the next phase of redevelopment—New Mizner would replace 246 rental units with 500 condos—and the council and community should debate what should happen over the next 20 years.

“It’s great,” Mullaugh said, “that someone (Elad National Properties, in this case) has come up with something this far outside what we expected.” Indeed. Think more of Santiago Calatrava (the City of Arts and Sciences in Valencia, Spain) than Addison Mizner. “It’s definitely not what Boca has ever been.”

Which, as Weinroth sees it, is the problem. “It’s insensitive,” he said, “to ask the community to accept this. It’s going to take a lot to convince this council.”

Weinroth and Mullaugh agree that Boca Raton has to “digest”—Weinroth’s term—all the downtown development already approved. Mullaugh, though, sounds more willing to look ahead sooner.

13 years later

Especially after President Obama’s speech last night, everyone in Boca Raton and the area should take a moment today to remember the terrible events of 13 years ago. Even after more than a decade, the pain and anger linger.

••••••••

You can email Randy Schultz at randy@bocamag.com

For more City Watch blogs, click here.About the Author

Randy Schultz was born in Hartford, Conn., and graduated from the University of Tennessee in 1974. He has lived in South Florida since then, and in Boca Raton since 1985. Schultz spent nearly 40 years in daily journalism at the Miami Herald and Palm Beach Post, most recently as editorial page editor at the Post. His wife, Shelley, is director of The Learning Network at Pine Crest School. His son, an attorney, and daughter-in-law and three grandchildren also live in Boca Raton. His daughter is a veterinarian who lives in Baltimore.