Delray fire rescue decision reached

There is not yet finality to all issues with the Delray Beach Fire-Rescue Department, but there is much more certainty about how to resolve those issues.

Most important, Delray will resolve them. Last week, the city commission rejected for the foreseeable future any talk of contracting with the county’s fire-rescue department. “The numbers just didn’t add up,” Commissioner Mitch Katz said. City Manager Don Cooper and Fire Chief Danielle O’Connor will produce a plan that addresses complaints from the International Association of Firefighters, not all of which were valid.

Regarding the union, however, there is progress. IAFF Local 28 has ratified a new contract with the city. The commission will approve it next week. Under the deal, Delray Beach will stay in the state program that provides the city with about $1 million per year toward the fire/police pension fund from an assessment on insurance policies. The union will allow the city to use that money toward unfunded pension liabilities, not new benefits, despite a 1999 state law directing it toward benefits.

Accepting that money means that cities also must accept rules on the structure of local pension boards. In Delray Beach, as in Boca Raton, two fire and two police representatives sit on the eight-member boards that decide how to invest the fund’s assets. Although Delray is responsible for any fund shortages, the city has no effective control over decisions that could create a shortage.

Mayor Cary Glickstein had wanted to leave the state program, so the city could change the board. Cooper said the firefighters union has agreed to changes in the board makeup that would give the city more say. In addition, Cooper said, the contract lowers the multiplier—the number used to calculate pension benefits by length of service and salary—from 3 percent to 2.75 percent and slows benefit levels. “We got a very good response from the union,” Cooper said.

Glickstein agrees. He said the fire and police contracts will provide the city about $2 million each year to shore up the pension fund. The fire pension board will have the same attorney, fund managers and actuaries as the general employees pension board. There could be a separate police pension with the old structure, Cooper said. Or the police union could agree to the new rules for a combined public safety pension board. “I’m very pleased,” Glickstein said, adding that Delray Beach is the only city in Palm Beach County to have reached such a deal.

The firefighters’ contract took a year and a half to negotiate. Though it’s a three-year deal, it will expire on Sept. 30, 2017 and will be retroactive to Oct. 1, 2014. Between this contract and the new contract with the police union, the commission can say that it has done much to make the fire-police fund sustainable over the next 30 years—the industry standard for review.

That has been a commission goal. In its most recent review of municipal pension programs, the LeRoy Collins Institute at Florida State University gave Delray Beach’s police/fire pension fund a rating of ‘F’ and labeled it among the worst performing in the state. The institute bases its ratings largely on the amount of unfunded liabilities and investment performance. In contrast, Delray’s general employees fund got an ‘A’ rating.

With the contract set, Delray must begin to fill vacant fire-rescue positions—the city now can tell new hires who they will work for—upgrade facilities and equipment and decide what level of service the department will offer.

Staffing should move quickly. Katz said there are roughly 200 applicants for what Cooper told me are between 12 and 14 openings. The department also needs at least three new pieces of equipment. The number will increase to five if the city, as Cooper expects, and Highland Beach extend Delray’s contract to service the town.

In terms of facilities, Cooper refuted the union’s accusation that rats had infested Station 3 on Linton Boulevard, requiring an immediate move. The city and the union agree, however, that the city must replace Station 3. Cooper said the city has identified some nearby locations, which he declined to name, to avoid pushing up the price. He said the city has set aside $6 million to buy the land and build the new facility, which will include a training center. Cooper would like to break ground next fall.

Regarding level of fire-rescue service, three people ride on fire trucks and two are on emergency medical vehicles. Those numbers could go up—the union would like that—if the level of service goes up. There is debate, however, about how much return departments get for raising the level of service, which raises operating costs.

Cooper has asked O’Connor to compile a service-level report, which he hopes to have for the commission early next year. If the commission decides to spend more, staff can factor that decision into next year’s budget. But the commission already has made the big decision on fire-rescue—to keep a department—and it seems to have been the right decision.

Boca design guidelines

Anyone who accused the Boca Raton City Council of ramming things through without public discussion hasn’t followed the city’s attempt to set downtown architectural guidelines.

First, there was Ordinance 4035, in 1992. Then came Ordinance 5052, which added the Interim Design Guidelines. Developers who adhered to them could get extra height.

Then came The Mark at Cityscape, the mixed-use project that was the first to be built under the guidelines. When it arrived, all the expectant city officials disliked what their midwifery had produced. Some residents compared the building’s look to a prison.

So then came an all-day discussion—with council members attending as observers—last April of who was to blame. The city’s consultant, Urban Design Associates of Pittsburgh, which helped to create the guidelines? City staff, which reviewed the plans? The Community Appearance Board, supposedly the stickler for making Boca look good? All, to a degree, probably. And then, finally, came the follow-up discussion Monday before the council acting as the community redevelopment agency.

Interestingly, we have seen since April that the Hyatt Place hotel rising next to it will mostly block the most disparaged section of the Mark—its northwest exposure. The hotel itself was designed using the guidelines.

Some residents—the usual suspects—want the council to repeal Ordinance 5052. There isn’t sentiment for that, and it would be the wrong move.

Instead, the council wants to modify the guidelines and have a staff member or a contractor with expertise in architecture monitor such projects. “I think there’s a recognition that we need to move to a permanent solution,” Councilman Robert Weinroth said. “I would be pleased to find some resolution,” understated Mayor Susan Haynie.

To head off any more unpleasant surprises, the council asked the staff to check on the two other projects being built under the guidelines—the hotel and Via Mizner. Meanwhile, discussion about the guidelines will continue.

Of course.

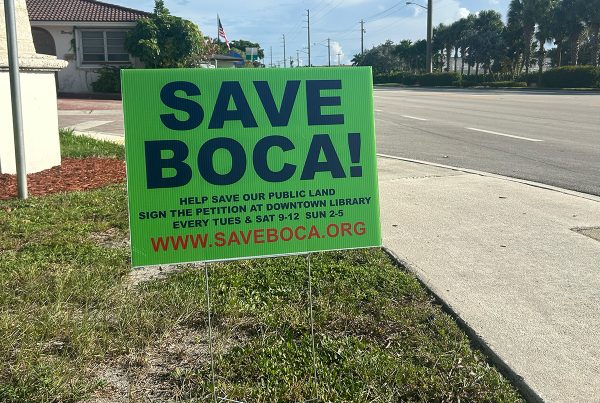

More on University Village

The Boca Raton City Council took no vote after Tuesday’s first public hearing on University Village, but the developer made a credible case. A vote to approve or reject the project will take place on Nov. 24.

Planning and Zoning Director Jim Bell confirmed that the project along Spanish River Boulevard north of Florida Atlantic University would generate less traffic even though it would have a higher density that similar Planned Mobility Developments, which are designed to encourage transportation alternatives to cars. He also told council members there would be a “long buildout” on the 77-plus acres, with site plans for each phase coming to the council. Though one resident of a nearby neighborhood caustically predicted that University Village would become “an FAU slum,” a representative of the developer said the target market would be college graduates and up, all the way to Baby Boomers who “have mowed their last lawn.”

On the west side of the site is the El Rio Trail, which has become a popular cycling route. The project would include public parking for the trail. The developer’s lawyer said University Village could include entrances from neighborhoods to the east, for residents who wanted to get to stores or restaurants or go through the project to the trail.

Mayor Susan Haynie ended the uneventful presentation with a “suggestion” that the developer meet with those potential neighbors before the second public hearing. The developer probably would be smart to consider that more than a “suggestion.”

What Missouri and FAU have in common

I had a flashback this week when the University of Missouri forced out President Tim Wolfe.

Wolfe had been in trouble for failing to respond to complaints by African-American students about racial harassment. But when protesters confronted Wolfe’s car during the homecoming parade, demanding to speak with him, Wolfe tried to drive around the students. In doing so, he clipped one with his car.

Sound familiar? Recall the protests at Florida Atlantic University when FAU announced that GEO Group—the Boca Raton-based operator of private prisons and detention facilities—would spend $6 million to have its name on the football stadium. Saunders basically brushed off those complaints. After taking questions from students for an hour, she bolted from the meeting.

Then a group of students approached Saunders as she drove from FAU’s Jupiter campus. Rather than do the smart thing and get out, Saunders kept driving—and bumped one student with her car. She then retained a security detail. Two months later, she was out.

Tim Wolfe was hired because he had been a CEO, and some trustees want presidents who run universities like businesses. Students, though, are not stockholders. Presidents can’t hide from crises. Wolfe might have his job if he hadn’t followed Saunders’ bad example.

Plane crash

Boca Raton got jolted Wednesday with word that seven employees of Pebb Enterprises had been on the plane that crashed in Akron, Ohio. The private equity real estate firm has been in its headquarters building near Glades Road and the Florida Turnpike since 2010. Understandably, the company was taking no questions from reporters. A city’s thoughts and prayers go out to the victims’ families.