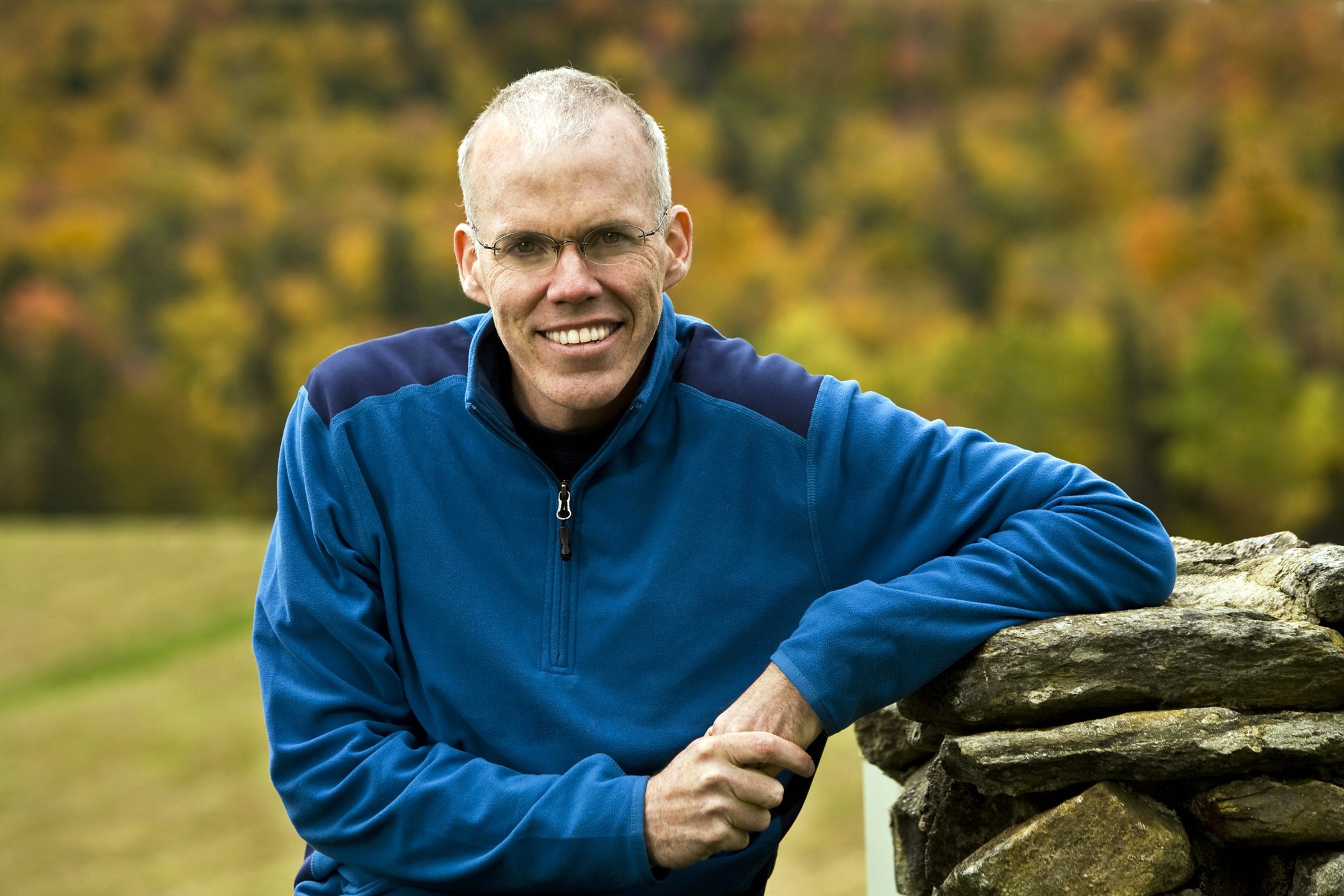

The fossil fuel foe is still fighting the good fight, more than 30 years after sounding the first alarm.

For all the attention Al Gore has brought to environmental issues, he hasn’t yet had an entire species named in his honor. Bill McKibben, on the other hand, was able to scratch this off his bucket list in 2014, when biologists christened a new species of woodland gnat the megophthalmidia mckibbeni.

It was a sign of just how deeply McKibben’s activism has penetrated the earth sciences. His 1989 book The End of Nature was the first clarion call about climate change written for a general audience. He’s penned a dozen books since, while running the influential nonprofit 350.org to spur action to curtail global emissions and divest from fossil fuels.

One of the highlights of the in-person return of Festival of the Arts Boca, McKibben will take the stage of Mizner Park Amphitheater during a particularly prolific period: In 2020, he published Falter, a cautionary tale of our headlong rush into robotics and artificial intelligence; and he’s finishing his next book, The Flag, the Cross, and the Station Wagon: A Graying American Looks Back at his Suburban Boyhood and Wonders What the Hell Happened. “As you might imagine, it’s in part about the ways our postwar prosperity curdled into something that’s damaged both the environment and our democracy,” he says.

At his Festival of the Arts presentation, he adds, “I will describe our new work, starting an organizing drive called Third Act, for people aged 60 and above. We’re determined to show that people of a certain age … can bring their experience, resources, and talents to bear on behalf of the future.”

What spurred your climate activism?

I wrote the first book on climate change back in 1989—and for many years I thought that writing more books and giving more talks was my main task. I assumed that if we piled on enough evidence and data that eventually our leaders would act—why wouldn’t they? But eventually, after about a decade, I came to realize that while we had won the argument about climate change we were losing the fight, because the fight wasn’t about science; the fight was about money and power (which is what fights are usually about). And the fossil fuel industry had so much money, and hence so much political power, that they were able to keep action at bay. So that’s when I and others started organizing big grassroots movements, knowing that we somehow needed to match the power of the Exxons of the world.

How does the rise of artificial intelligence, which you address in Falter, factor into global climate change?

I’m not sure it does—but it is another example of going pretty heedlessly down a path that we haven’t fully examined. We’re not very good, in our collective life, at restraining ourselves, and so here we are not setting any boundaries for technologies of enormous power.

In 2016, you were part of the committee to write the Democratic Party’s platform. In the years since, how has the party followed up on its goals, particularly on climate?

Biden has made serious attempts to get real climate action, and he’s brought 48 or 49 senators along with him. As we’ve seen too clearly, that hasn’t been quite enough: Joe Manchin has continued to do the bidding of the fossil fuel industry, dramatically weakening the administration’s efforts. But I think Biden deserves real praise for trying.

Do you believe that passing sweeping legislation such as the Green New Deal is necessary for our future? If so, should the “price tag” of such legislation be an important part of that discussion, as many of its critics offer?

The price should definitely be a part of the discussion, as long as it’s an honest discussion. Which would mean calculating the cost of not doing anything—at the moment, the high-end estimate for the damages from unchecked climate change are $551 trillion, which is more money than currently exists on planet Earth. Meanwhile, the latest studies from Oxford University show that the Earth would save tens of trillions of dollars by a rapid conversion to renewable energy, even without calculating the damages from climate change—simply because the sun is free and oil isn’t.

As Falter suggests, the present seems bleak. How do you remain optimistic about the future?

I don’t always. But the rapid fall in the price of renewable energy, and the rapid rise in movement building, seem to me to offer new possibilities for quick change. If we can get older Americans backing up youthful leaders in this fight, I think we might surprise ourselves at how quickly we can make change.

IF YOU GO

WHAT: Bill McKibben: Our Changing Climate

WHERE: Mizner Park Amphitheater, 590 Plaza Real, Boca Raton

WHEN: March 8, 7 p.m.

COST: $35, or $10 for virtual stream

CONTACT: festivalboca.org

This article is from the February 2022 issue of Boca magazine. For more content like this, subscribe to the magazine.