Readers of this blog may recall regular references to the importance of cities emphasizing what residents can’t see.

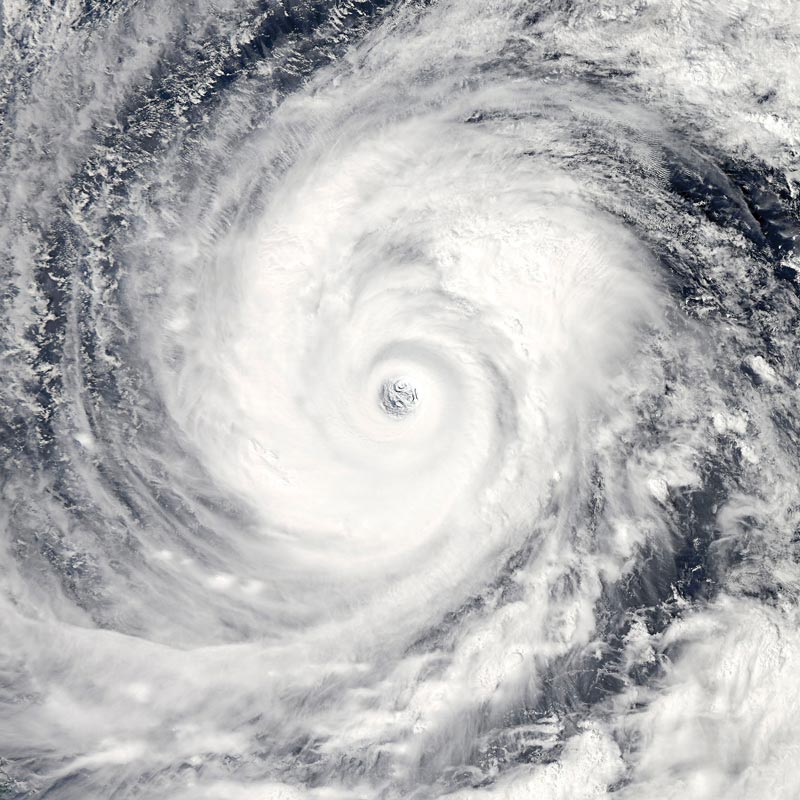

That means the underground systems that deliver water, get rid of water and keep sewage—formerly known as wastewater—from going where it doesn’t belong. Nothing tests these systems like a tropical cyclone.

Fortunately for South Florida, Hurricane Ian slanted northeast across the state after landfall near Fort Myers and the worst of the storm missed this area. Boca Raton got four inches of rain. A city spokeswoman said the only flooding problems were those from a standard thunderstorm.

City Manager Terrence Moore said Delray Beach had only “localized” flooding in “the usual places,” which tend to include the Marina District and other low-lying neighborhoods where tidal flooding is routine. Moore said Wednesday that he’s still “assessing” and will update city commissioners in his weekly newsletter that comes out Friday.

Close encounters, though, can remind local officials of the need to determine whether their cities could withstand deluges like those Ian dumped elsewhere. Parts of Orlando got between 12 inches and 15 inches. Sanford, northeast of Orlando, got 16 inches. New Smyrna Beach, near Daytona Beach, got 21 inches.

Before Ian, Lake Okeechobee’s level was very low for this time of year. The executive director of the Lake Worth Drainage District, which covers southeast Palm Beach County, worried about supply. Ian’s rains raised the lake level by two feet.

The wakeup storm I remember is Irene in 1999. It came up the spine of the state as a borderline hurricane with tons of moisture on its east side. Boynton Beach’s stormwater system, which the city had considered adequate, failed. It took several rounds of stormwater assessments to upgrade the system.

Moore also remembers Irene because he was city manager in the Brevard County city of Sebastian. Moore acknowledged the “topographical challenges” in Delray Beach, which previously heard from a consultant that it could take nearly $400 million to protect the city from the effects of rising seas.

Delray Beach, Moore said, must invest regularly in construction projects to prevent flooding. Cities must have enough generators to keep lift stations—which move sewage through the system—operating if power goes out.

Boca Raton has done well during recent brushes with hurricanes. Water and sewer service never failed. With climate change likely making storms wetter, though, cities may have to adjust worst-case scenarios for what their systems can handle.

Commissioners and DDA to discuss OSS deal

I wrote Tuesday about early plans for the Downtown Development Authority to operate Old School Square in Delray Beach. Moore met Monday with DDA representatives.

Moore said Wednesday that the city commission and community redevelopment agency—on which the mayor and all four city commissioners serve—will meet with the DDA to work out an agreement to cover the agency’s role. There is no date, but Moore wants the meeting “as soon as possible.”

The heart of that agreement will be how much money the city must spend to reopen the Cornell Museum and Crest Theater. Moore noted that city staff work on such popular outdoor Old School Square events such as the holiday tree lighting. Moore would not estimate how much the new cost will be after the commission fired Old School Square for the Arts.

Delray budget debate

Every year when discussing Delray Beach’s budget, city commissioners argue over how much to keep in reserves, known as the “fund balance.” The city wants to give those arguments more substance.

Some commissioners argue that hurricane-prone cities should have more reserves. Others respond that the money could go into the budget and allow the city to cut the tax rate.

In general, Delray Beach has put aside one-fourth of its operating budget—the one that finances police, fire and parks—in reserves. There are separate reserve funds for the water/sewer and garbage budgets that rely on property taxes.

In a Sept. 29 email, Finance Director Hugh Dunkley said he wants to craft a proposal “to indicate what level of fund balance/working capital we feel would be adequate for the city’s major funds.” Expect a lot of arguing over that proposal.

Boca’s House seat race most expensive in PBC

The race for the Florida House seat that includes Boca Raton is already the most expensive in the county and could wind up as the most expensive in the state.

Democrat Andy Thomson, who sits on the Boca Raton City Council, is facing Republican Peggy Gossett-Seidman, who sits on the Highland Beach Town Commission. Thomson has raised roughly $250,000 directly, which includes a $30,000 personal loan. Gossett-Seidman has raised about $300,000, including a loan of $200,000.

In addition, the GOP is running TV ads for Gossett-Seidman. In addition to Boca Raton and Highland Beach, the district includes portions of West Boca, which tend to be more Democratic. President Biden carried the district by 4.5 points.

For more than two decades, a Republican has represented Boca Raton in the House. Redistricting, however, forced incumbent Mike Caruso into a race farther north. Though Republicans already have a 78-42 advantage in the House, they are trying very hard to retain this particular seat.

Boca’s self-financed city commission candidates

Speaking of elections, Boca Raton’s next March is shaping up as one of self-financed campaigns.

Though Francine Nachlas is so far unopposed for Seat A, she has loaned herself $50,000, making her overall contribution total $77,000. Nachlas is running to succeed Thomson, who must resign from the council win or lose in the House race.

Mark Wigder and Christen Ritchey have filed for Seat B to succeed term-limited Andrea O’Rourke. Wigder has loaned his campaign $60,000. His overall total is $63,000. Ritchey has raised $17,000.

All these totals are through August. I’ll update when the city posts the September reports.