“I won’t let Miami be rebuilt on half-baked pyramid schemes.”

Maurice shrugged. “That’s how it was built in the first place.”

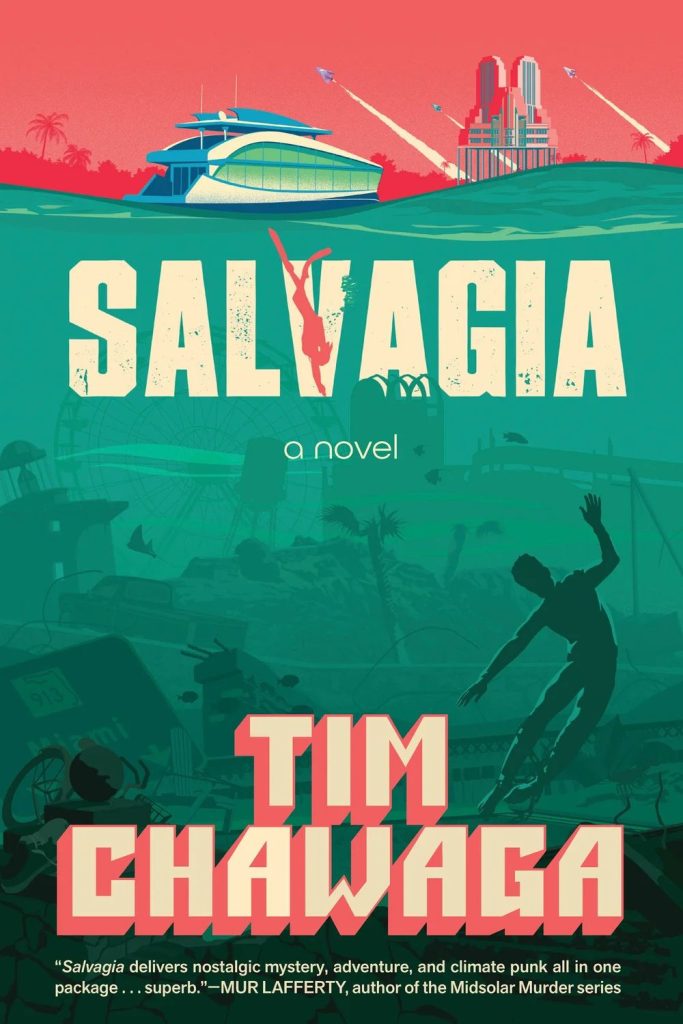

Florida readers will identify with many such exchanges in “Salvagia” (DIversion Books), the debut novel from Brooklynite Tim Chawaga. Released in August, this speculative sci-fi murder mystery is set in a future South Florida, where climate change and routine monster hurricanes have left our present paradise largely unrecognizable.

With the federal government and “corporate mafias” jockeying for power on what’s left of the land, our protagonist, Triss, a former federal employee, survives on a semi-sentient yacht, from which she dives for “salvagia”—relics from our current life of plenty, buried in the depths of the Atlantic Ocean or the crannies of the myriad shipwrecks lining its floor, that have become valuable collectors’ items. When she discovers the body of Florida’s most powerful “mafioso” floating in the “yoreshore” of Key West, she becomes immersed in a conspiracy that could disrupt her plans for a peaceful future on her AGI-powered vessel.

In this conversation with Boca magazine, Chawaga discusses the influence of the eminent Florida crime writer John D. MacDonald on his work, the challenge of sci-fi world-building, and why he doesn’t see his novel as a dystopia.

Do you have any personal connection to Florida?

I grew up going to the Tampa Bay/St. Pete area every year when I was a kid. Aside from that, no. … The thing that I am really connected to with this book in particular is the series that inspired it, the Travis McGee series.

Right, you mention in the afterword that the late John D. Macdonald “taught you how to write this book.” What do you mean by that?

I’ve read the first book in the Travis McGee series, “The Deep Blue Good-by,” probably six or seven times now. The thing that I was really trying to do when I wrote the first draft of this book was a sci-fi version of “The Deep Blue Good-by.” And that’s impossible, for lots of reasons. It’s really hard to write science fiction in the incredibly tight John D. MacDonald prose style, which is very efficient. But attempting to do so definitely made me a much better writer. Trying to be like him, and trying to write plot with the sort of efficient rhythm that he does, definitely improved a very world-building science fiction book that, in its first incarnation, was like 450 pages.

Why is Florida the perfect location for a novel like this?

Florida is, I think, historically, currently and in the future, one of the most susceptible-to-scams places in America. The thing that interests me so much about Florida is the way the rest of the country perceives Florida. It’s a repository for the dreams, the ambitions, the scams, the pitches for everyone else in the country to go to and use it to be that. And so I think it’s a really great place to imagine where the country will go and what will happen to a lot of the people who will move, who want to move, who must move as a result of climate change.

There’s a line of dialogue in your book: “Every generation or two, an American demographic in search of paradise will ‘discover’ Florida—in particular its resistance to regulation.” We saw that happen in a big way during COVID when a lot of people moved here from high-regulatory states. But is the book saying that this resistance to regulation is also our downfall, when it comes to climate, and when it comes to “corporate mafias,” as you call them in the book, running things?

For the most part, probably yes. One thing that I was trying to spend a lot of time trying to give room for in this book was the idea of a third way, like an alternative way of living—in between full regulation, like federal regulation, and complete deregulation. So I don’t know if I’d necessarily call my vision for the future here particularly optimistic, but I wanted to leave room for this idea that a new thing could exist, and it can only exist at a time where significant change is happening, like on the cusp of a deregulation boom, a property boom, in places like Florida, where it is a boom-or-bust place historically, in a lot of ways. That level of drama, of dramatic change, also leads to opportunities, but I wanted to keep some room for that in this book.

Given that’s a Florida-set futuristic sci-fi, I admire your restraint in waiting until page 19 to introduce a mechanical gator.

It would have come in page one, if I could have found a way for it to make sense.

This book began as a short story, then a novella. From its earliest form, what compelled you that there was more to explore here?

I would like it to be, ideally, a whole series. Once I started building the world, I just kept having ideas for things that could happen in it, or places that it could go. And it really became too tough to contain it all to a short story. But I think the more I expanded it, the more I wanted to keep writing in this world. My ambition as a writer has always been to create a sandbox that I can return to. And so creating a bunch of rules that I think are fairly sustainable, in that way, I just wanted to keep going, to keep fitting stuff into it, to the point where I had to pull back. Going back to John D. MacDonald’s mastery of efficient prose really helped me, once I had all of those things, to constrict it back down and keep me focused on the railroad track.

You mentioned world-building a couple of times. I have a special admiration for writers who set work in the future, because it takes a depth of imagination. When you were world-building this book, what are some of the ways that you looked at where we are now and then imagined where we will be—not just as Floridians but as a society?

As I was saying, I wanted to keep a little room for an alternative way of living. Based on how I’ve shown the role of the federal government and the role of the corporate mafias, what I think is that for the most part, people in the future will continue to live mostly normal lives. The thing that I was trying to avoid in this was displaying the future—a climate-change future in one of the most climate-vulnerable places in the country—as a dystopia, like a place that was uninhabitable, a place that was ruleless or lawless entirely, but also a place that was very ripe for crime fiction, where there were a lot of opportunities for people to take advantage of each other, just like there are today. But the thing I wanted to make clear was that while people will be living differently and perhaps more or less desperately, they will be continuing to live, and finding ways to pursue the things that they want, to imagine new things, to imagine their present, not just nostalgize the past or lament what happened in the past.

There are competing interests in this book—the Church of the Invisible Hand, the Mourners of Miami, and the Floating Aquatic Co-Op, while the feds want to put everyone in Consolidated domes. That word Consolidated has a sinister Orwellian tone to it. Did you take anything from Orwell, Huxley and the other dark futurist writers when you were conceiving the book?

Not specifically. The idea of big government control is something that was a lot more prevalent at their time in their writing. Where I think that, in American science fiction, cyberpunk is much more concerned with corporate dystopia, capitalist exploitation, stuff like that. And I think that this book has some elements of both of those things. This book very much thinks that any system that is big enough will find a way to exploit you, and does exploit you, and does it in ways that are definitely akin to the ways that we’ve seen in science fiction in the past. But mostly it doesn’t believe that there’s any big system that’s good, particularly. One might be slightly better than the other, like Consolidation. The characters mention that a benefit of it is that by subsidizing everybody’s housing and food, you really do have the ability to create a working middle class. Giving people the things that they need actually does help in that way. But the methods to do so are, for sure, oppressive.

Why are salvaged everyday objects such a sought-after currency in this world, to take it back to the title?

What’s cool about it is that nobody’s entirely sure yet. We know that they have value. People like Triss, who are trying to make a living trying to get these objects, know that they’re valuable, and know what is valued. But even to her, she’s not entirely sure why. She thinks that it’s maybe related to its pure aesthetic value, that you can see the difference between what this object looked like in its prime when it was above water, and how it has decayed.

And there’s something about that contrast that’s interesting. And I spent a lot more time thinking about what the characters currently think about salvagia. I’m a lot more concerned about the thematic value of this idea of an object that has increased value because of how much it has been ruined, and how that’s a symbol for what these people think of the past. They essentially think about the past as, what can it do for us now? What can the idea of nostalgia do currently for us to advance our mostly fiscal goals?

Coral Castle is a place of some significance in the book, as a dream of communal living surrounded by these extraordinary megalithic structures. How did you come to include this site as an important location?

I think it’s just something I came across while I was looking for locations—striking landmarks in that part of Florida. And I’ve actually never been to it. I’ve just looked at all of the pictures of it. It’s so Stonehenge-y, and imagining it as a ruined thing in the future made it feel even more monolithic.

At the end of the day, this is a murder mystery. Even though it’s set in a sci-fi future, are there still basic story elements that have stood the test of time, that date back to MacDonald’s era, that you just have to adhere to as a mystery writer?

You don’t have to, but depending on what your objectives are, it’s way easier to. In chapter one of my book, there is a dead body, and that’s classic murder mystery 101. You don’t need to do that. And actually, often John D. MacDonald doesn’t even do that. The great mystery writers know how to create that suspense and that tension without something like that. But the easy, can’t-go-wrong shorthand, for sure, is to drop a body in chapter one, and then drop more bodies thereafter. There is a 12-step murder mystery formula that I read. It’s very formulaic but very helpful in that way. It’s important to both understand what those beats mean and how they keep tension and how they enhance your story, and how they build suspense. And it’s also important to know when you can break them, and how you can break them in interesting ways.

For more of Boca magazine’s arts and entertainment coverage, click here.