For all of the strides the United States has made toward racial justice since the dawn of the Civil Rights Movement, few would argue Madison Avenue has led the charge toward a more perfect union. Corporate advertising, a surface-sunny profession that prefers positivity to negativity, is also an untrustworthy business where the motives of the admen are driven not by a desire for national comity but to advance the machine of commerce. If inclusivity is part of the message, it’s because inclusivity sells.

These are a few of the thoughts that bubbled while viewing Hank Willis Thomas’ sweeping exhibition “Unbranded: Reflections in Black by Corporate America,” the centerpiece of the Boca Raton Museum of Art’s multipronged “Myths, Secrets, Lies, and Truths: Photography from the Doug McGraw Collection,” running through mid-October. I’ll be focusing this review on “Unbranded” because it’s an important stand-alone show that consumes the most gallery space by far.

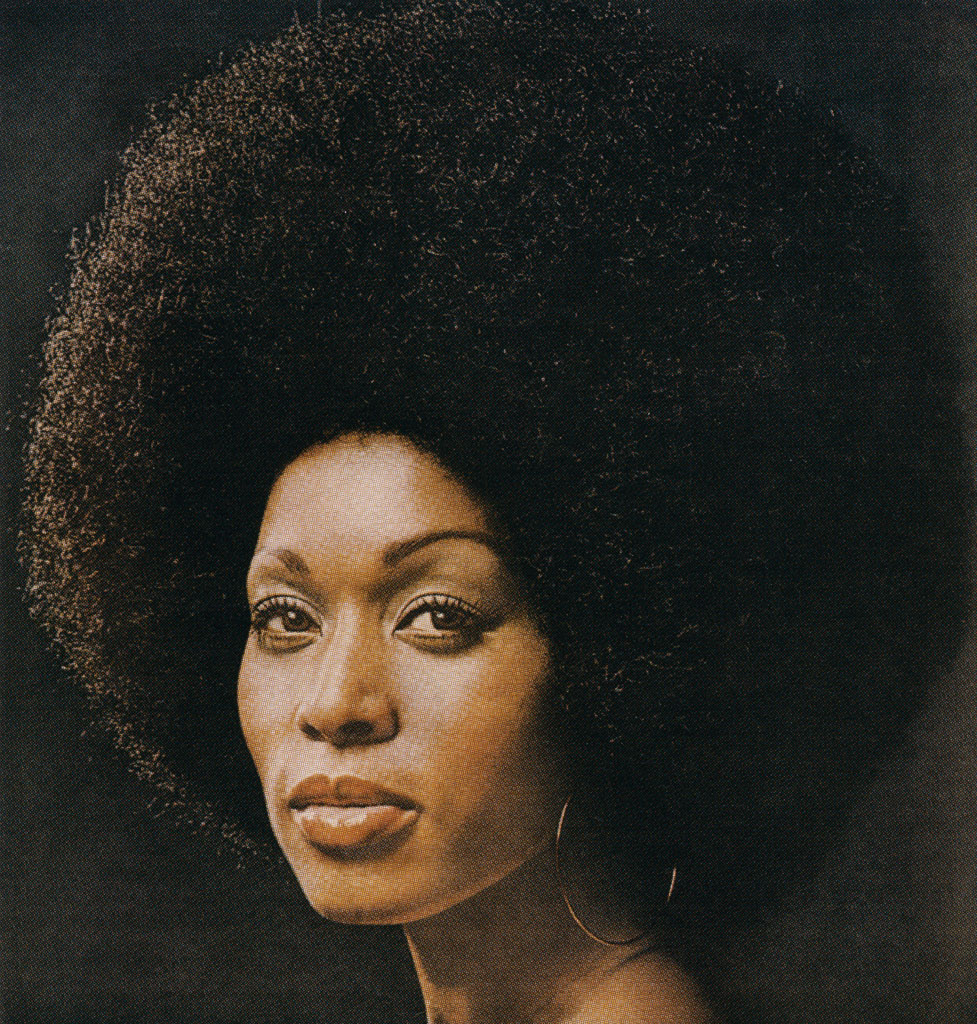

Thomas’ work is based on a simple but genius idea: Remove the branding from a work of advertising, and letting the chosen imagery speak—or scream, or dog-whistle—for itself. Thomas framed the series around pivotal tent poles for civil rights, beginning in 1968 with the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., and ending in 2008 with the election of Barack Obama.

Part of the show’s commentary reflects the (d)evolution of advertising itself, from a more, you might say wholesome, prerogative toward an opening, in the 1990s and aughts, for exploitive visuals that border on pornography. So it goes that a ‘60s airline ad titled “We Are On Our Way,” a multicultural idyll in which white and Black families happily converse amid the common denominator of coach, gives way to an image in which a rosy-cheeked woman seems to derive sexual gratification from a sneaker.

I rather liked “We Are On Our Way,” which strikes me as the best of what advertising can do as a forecaster of progress. At least it projects a more unified world, even if its motivations are tacky. I found a certain sweetness in many of these works, in fact; in “Love Hang-Over,” which could be an ad for headphones, a Black couple nuzzles while listening to records, a portrait of domestic tranquility. In “Pucker Up,” two Black models link their cigarettes together, like the famous pasta scene from “Lady and the Tramp,” under a blanket of white negative space; it’s just a cool image, if you can put aside its pernicious promotion of cancer sticks.

Likewise, “Jungle Fever,” for all the crassness apparent in its title, shows Black and white fingers intertwined in a legitimately beautiful work of art. And there is much to be admired in the daring “Power is Nothing Without Control,” an early 2000s ad which features a gender-bending Black cis male in red heels, in a crouching pose, challenging notions of gender fluidity that are still not accepted in many parts of the country.

More often than not, though, the creators of these advertisements—mostly white men, it’s safe to assume—can’t help but perpetuate degrading stereotypes, even when (especially when?) they’re trying to cater to the desires of Black America. “Are You the Right Kind of Woman For It?” poses a question whose answer, apparently, is a Black pimp-like figure surrounded on both sides by white female concubines. Lord knows what’s actually being sold here, except a lifestyle of excess informed by Blaxploitation cinema. “Available in a Variety of Sizes and Colors,” another ad whose actual product is mystifyingly oblique, shows a Black man in a buffet line leering at the bare legs of a fellow female partier, perpetuating the notion that the ogler, and by extension the Black male writ large, only has one thing on his mind.

There are works that play even more explicitly to racial divisions and the perceived differences in sexual virility. In “The Mandingo of Sandwiches,” a square white guy at a bar, nursing a pallid sandwich, admires the sloppy joe being enjoyed by his grinning Black neighbor. When the text is this offensive, who needs subtext?

As late as 2003, ads callously exploited freedom fighters and America’s history of enslavement by suggesting that a product could rectify it all. But by and large, the later pieces in “Unbranded” are less bothersome—if no less transparently tacky—than their forbears. Irony, postmodernism and sheer aspiration can, on the surface, smooth over the more troublesome implications of the earlier ads. “Membership Has its Privileges” reverses generations of racial hegemony in this country by offering a white servant standing in the rain with an umbrella, awaiting a Black child to exit her family’s luxury car. Works like this feel good, like a long-overdue correction, even if they do nothing to address the systemic racism that continues to arrest progress on racial equity.

And that’s the thing about even the less offensive works in “Unbranded.” They are not activism. They don’t offer food for thought. They reflect the zeitgeist only when it can benefit their shareholders. One of the last images that had an impact on me coincided with the era of Obama’s election. “Your Skin Has the Power to Protect You” is a Busby Berkeley dream of multiracial bare legs all in formation—a harmony of skin, jubilant for the dawn of post-racial America. If only it were so.

“Unbranded” runs through Oct. 13 at Boca Raton Museum of Art, 501 Plaza Real, Boca Raton. Admission is free through the month of September. For information, call 561/392-2500 or visit bocamuseum.org.

For more of Boca magazine’s arts and entertainment coverage, click here.