Observing a great artist’s workspace is a privilege to which few have access—dealers, collectors, the occasional journalist and, in the case of the Norton Museum’s “Artists at Work” exhibition, fellow artists. A small exhibit pulled from the Norton’s permanent collection, “Artists at Work” largely satisfies our imaginations of the classic studio setting, lending visible shorthand to the artists’ labors: tables cluttered with tools and stacks of books, extinguished tubes of paint littering the floors, coveralls spattered in splotches of color, canvases on easels in various degrees in completion.

The degree of tidiness in such spaces seems determined more by who’s creating these images of artists at work. Self-portraits have a more romantic and ordered sheen, while those composed by the subjects’ contemporaries have a messier honesty. In the former category, John Heliker’s “In the Studio” finds the artist rendered in thick impasto strokes, like many of his still-lifes and portraits, and showcases his love for bold color, from the blue of a skylight to the nature-green floor. Painter Robert Brackman’s self-portrait, in which he sports a sweater over a collared shirt—a still-life work visible behind him, his fingers on a brush handle—is the stateliest of the bunch, the closest example of an official portrait for posterity.

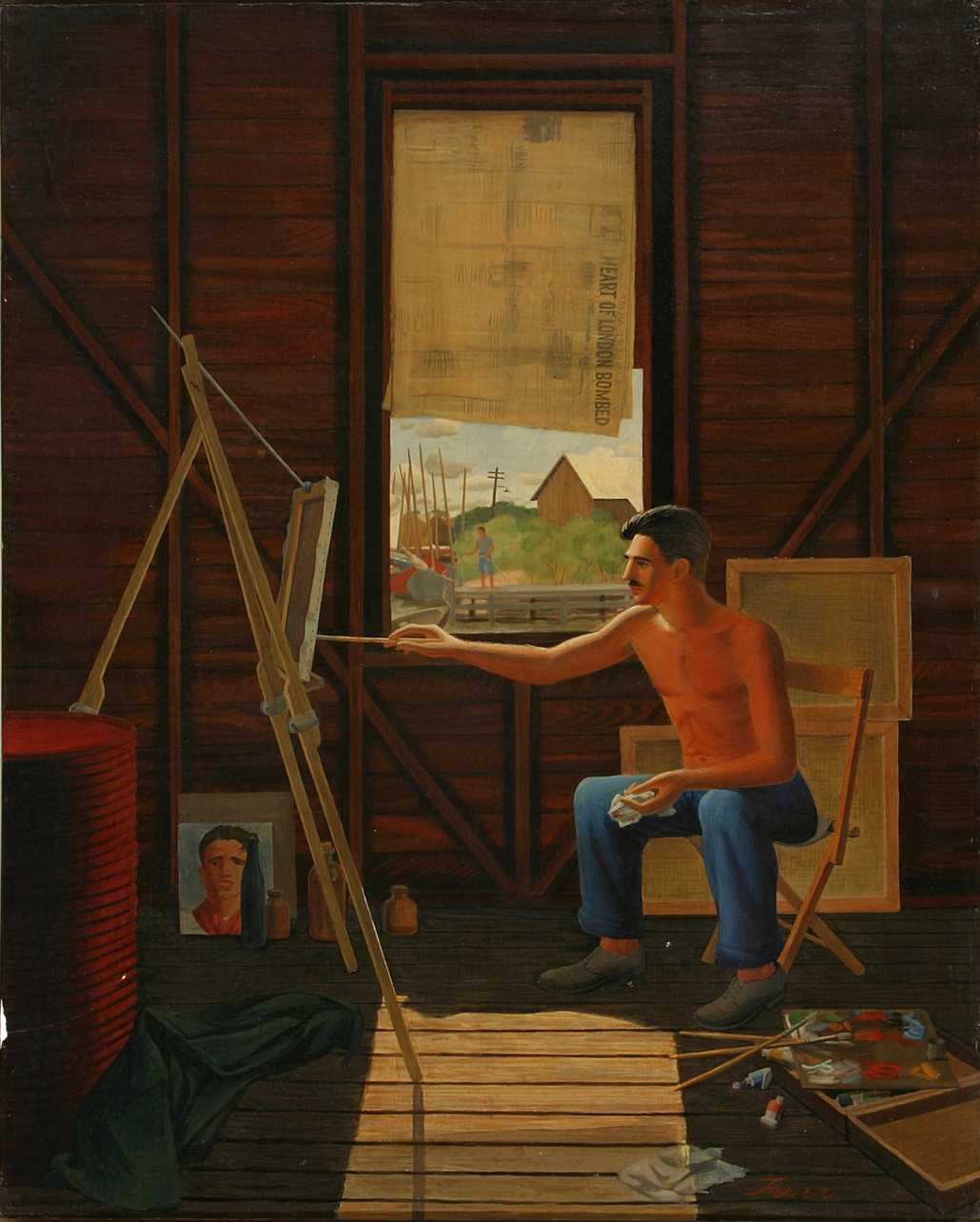

Similarly, Charles Griffin Farr’s “The Painter (A Self-portrait),” from 1941, feels like the most airbrushed of the bunch, but undeniably the most beautiful. Farr sits shirtless, touching a canvas with a brush, curated light filtering an autumnal glow through a partially covered window. A headline on the newspaper doing the covering—“Heart of London Bombed”—enforces the World War II contemporaneity of the painting, while through that square of open window, a person with a hose caters to their farmland. There’s so much Americana in this painting that it could almost be a Rockwell.

Photographers’ images of other working artists, by contrast, feel more accurate and less sentimental, if no less composed than the self-portraits. Their richness derives from their details as much as their framing: In a Robert Capa photo, Matisse, a cigarette adangle, contemplates a canvas, a studio wall filled with his drawings, the floor covered by newsprint. In Willy Maywald’s image of Georges Braque, brushes sprout from pots like flowers in bloom, the artist almost caught unawares under Maywald’s lens. While gazing at these works with heightened focus, it’s tempting to seek forensic evidence of how these talented men and women lived. What to make of the mussed blanket on a cot in Maywald’s photo of Fernand Leger? Did the artist sleep there occasionally?

Leave it to an avant-garde artist, however, to create the most idiosyncratic studio rendering in the exhibition, and a frontrunner for my favorite work in the show. Painter Hiram Williams’ “Big Studio Table” hardly appears like a functional piece of furniture; the table in question, which takes up most of the painting’s real estate, is concave in the middle. The abstract silhouettes of work implements that appear atop it resemble skyscrapers in a cityscape, while the frequent use of dripping paint reminds us we’re looking at a painting. “Big Studio Table” suggests that sometimes, the most personal renderings of an artist’s private space derive from jettisoning the familiar.

“Artists at Work” runs through June 21 at Norton Museum of Art, 1450 S. Dixie Highway, West Palm Beach. For information, call 561/832-5196 or visit norton.org.

For more of Boca magazine’s arts and entertainment coverage, click here.