Perhaps second only to his skill as a pugilist, Muhammad Ali was a peerless self-promoter. He was a pitchman whose most iconic bon mots read like poetry, complete with an innate sense of rhyme, as in his most iconic couplet: “Float like a butterfly, sting like a bee—his hands can’t hit what his eyes can’t see.”

The genius in this oft-quoted boast from Rumble in the Jungle is the dichotomy, perhaps unexpected in a sport with such a violent reputation, between gracefulness and aggression. To the layperson, the bee, with its tactical stinger, is endemic to boxing; the gentle butterfly, floating on gossamer wings, perhaps not so much.

The Norton Museum’s illuminating and seemingly comprehensive new exhibition on boxing bears a title that parallels the Ali adage. Covering a sprawling three galleries and subdivided into 11 sections, “Strike Fast, Dance Lightly: Artists on Boxing” doesn’t shy away from the element of hand-to-hand combat that has always been associated with boxing, but it spends as much, if not more, time on the delicacy, the dance, the flotation. It doesn’t reinforce stereotypes of the sport so much as subvert them. This tendency is evident right away in the “Tools” section that opens the exhibition, where Myloan Dinh’s “Tough Love” reimagines a punching bag as a construction of faux candy hearts, and An Te Liu’s “Restraint” depicts the same object as an hourglass-shaped leather bodice.

This upending of expectations extends to the final gallery in the exhibition, through works like Katherine Bradford’s “Boxers Under Lights,” in which faceless warriors embrace in a kiss; and Hernan Bas’s “Conceptual Artist #16,” whose combatants fight with pillows in a ring festooned with red bows, the feathered insides of their “weapons” fluttering around them as in a fairy tale. Nearby, Jeffrey Gibson uses Everlast-style punching bags themselves as his canvas, covering them with beaded messages of love, equality and empowerment.

In between these spaces, spectators grapple with nearly a dozen aspects of the sport through a variety of mediums, from painting and photography to sculpture, video and performance art. As befitting a blockbuster show, household names are plentiful, and one of the exhibition’s surprises is discovering how many world-class artists have been bewitched, intrigued and inspired by boxing and its vernacular.

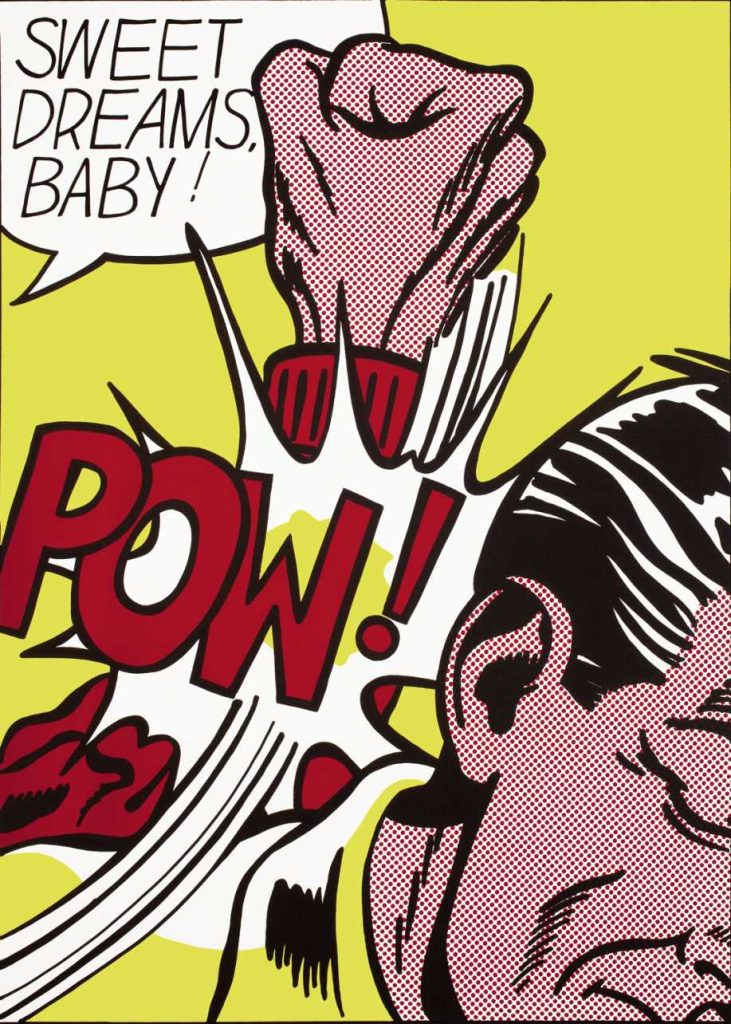

These include Ed Ruscha, with his droll textual art; Jean-Michel Basquiat, with his signature crowned avatars; Roy Lichtenstein, with his comic-book onomatopoeia; and Keith Haring, his squiggly figures rendered in sculptural form, either fighting or making love, however you choose to see it. Diane Arbus shows us a revealingly voyeuristic look at a boxer practicing in a New York City gym; and from Andy Warhol, we have a silkscreen of Ali with a blue superhero fist, transforming its subject into a cultural meme before we had the word for it.

Speaking of Warhol, he and Basquiat also turn up as the subject of a 1985 photograph by Michael Halsband, who staged an image of the two modern-art provocateurs, in Everlast shorts and boxing gloves, their arms crossed over their chests. Seeing this incredible document of two men who would soon depart this world effectively cosplaying as warriors, I was reminded of the way boxing can bring people together—just like it joined Ali and the Beatles for the famous 1964 Miami Beach photo op of the Fab Four taking a punch from the world’s greatest, also on display at the Norton.

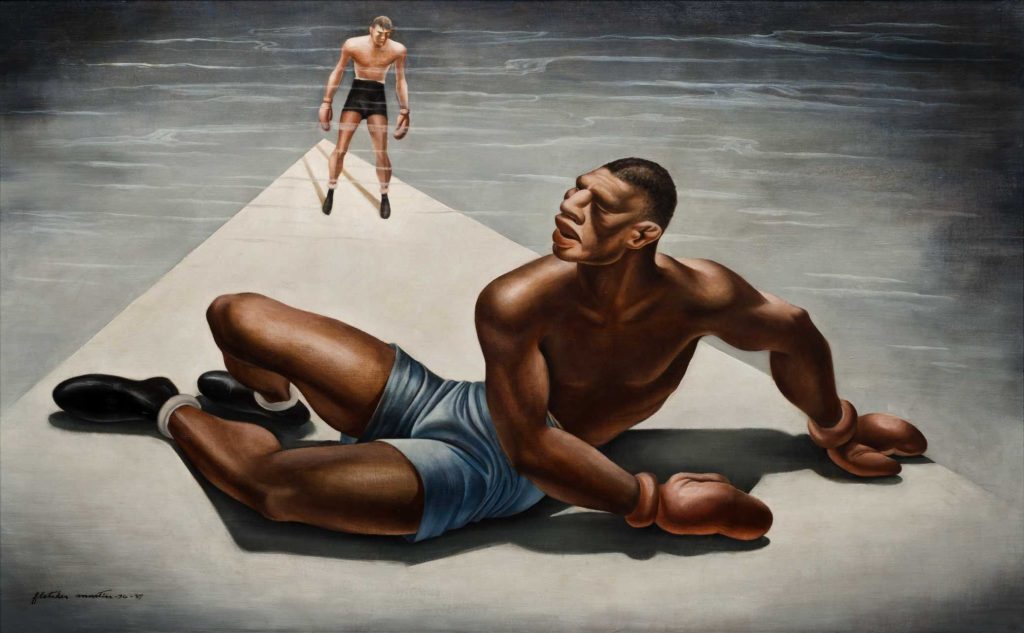

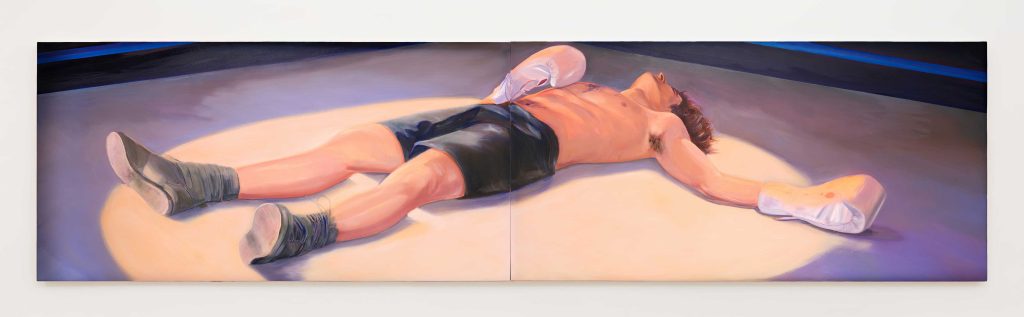

But some of the most memorable works in “Strike Fast” are from artists for whom I was unfamiliar—and that strip the sport of its braggadocio and machismo. The feeling of being on the losing end of a match is deeply felt in Caleb Hahne Quintana’s “How a Fall Can Make You Real,” which depicts a boxer flat on the mat, defeated under the harsh glare of a spotlight, in an eerie void where nothing else exists. Similarly, Fletcher Martin’s “Down for the Count” takes a more Cubist approach to its depiction of a fallen pugilist, who exists not in a traditional ring but a triangular liminal space.

Other highlights do not shy away from the brutal physicality of the sport. A short, looping video by Paul Pfeiffer reconstructs a match in which one fighter is removed, so we feel only a single boxer’s pain as he is pummeled by an unseen force—boxing’s existential weight bearing down on him. Dana Hoey’s video “Fighters” shows female boxers sparring on four screens, generating a hypnotic effect from their harsh, grunt-filled ballet.

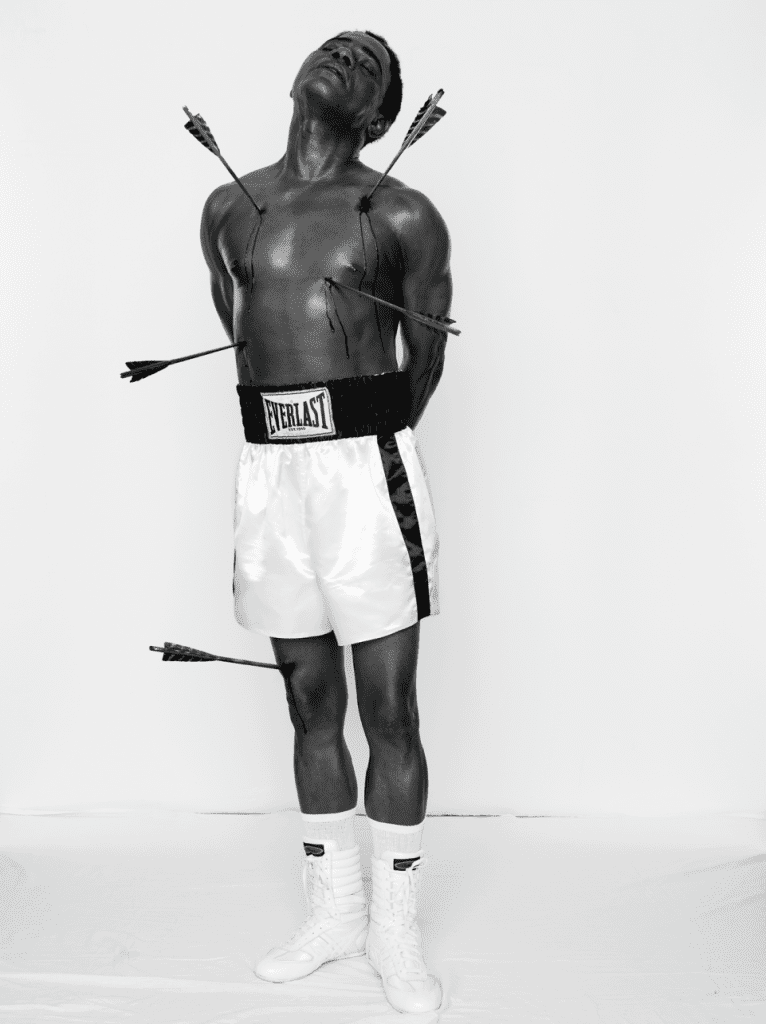

But the most powerful image in “Strike Fast, Dance Lightly,” to bring this alternately sacred and profane exhibition full circle, seems to show Ali, although it’s really the artist himself dressed in the boxer’s familiar apparel. In Samuel Fosso’s staged photography “Self-Portrait (Muhammad Ali),” part of a broader series, Fosso presents Ali as a martyr—the planet’s greatest athlete standing but slain by the literal slings and arrows of society, as a result of his outspoken politics.

I suppose, to reappropriate a term from the music world, that Ali was just supposed to shut up and box—to stick to being an entertainer. But if this exhibition shows us anything, it’s that boxing is not immune from the prevailing winds of society and culture and justice and masculinity. In the hands of artists both subversive and glorifying, it encompasses everything.

“Strike Fast, Dance Lightly: Artists on Boxing” runs through March 9 at Norton Museum of Art, 1450 S. Dixie Highway, West Palm Beach. Admission is $18 general and $15 seniors. For information, call 561/832-5196 or visit norton.org.

For more of Boca magazine’s arts and entertainment coverage, click here.