For the November/December edition of Boca magazine, we spoke with John Cutrone, longtime director of the Jaffe Center for the Book Arts, a growing compendium of art objects that test the limits of what a book constitutes. “These objects don’t necessarily look like books, and they certainly expand our ideas of what a book can be defined as,” Cutrone says. “But they are book in nature, and they’re often one-of-a-kind or very limited editions. If there’s some kind of border between traditional books and weirdness, we have one foot along each side of that border.”

Cutrone shared a few highlights from the collection in the article, but we wanted to dig a little deeper. In this exclusive web extra, we present five more selections that move, confound and delight.

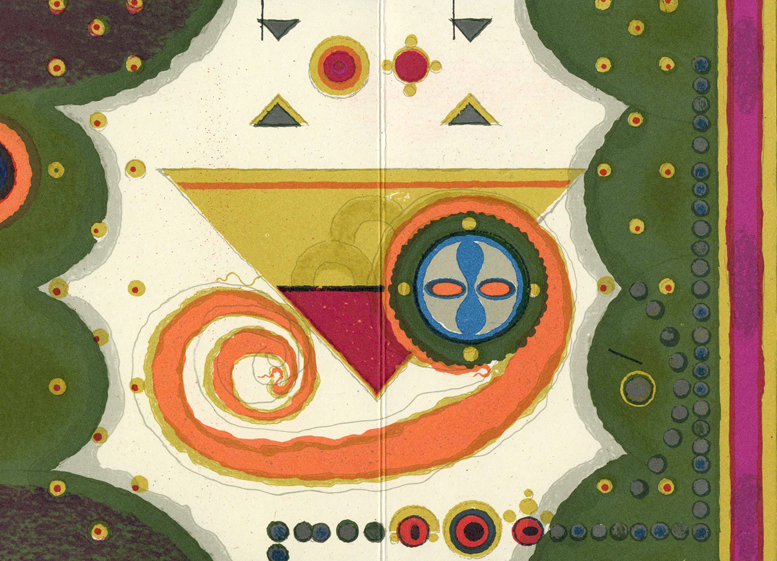

“Cendrillon” by Warja Lavater

Lavater’s singular book recasts Charles Perrault’s “Cinderella” fairy tale in a manner you’ve never “read” before: As a series of seemingly abstract paintings that are rich in symbology, allowing the reader to decode the familiar narrative. “Cendrillon” opens up like an accordion, allowing the reader the choice to view all the pages at once, or to peruse each page in bound succession, as in a traditional book. Either way, Lavater provides a road map of sorts—a legend at the beginning of the book, revealing Cinderella to be an hourglass-shaped figure contained within a circle; her prince to be an upside-down multicolored pyramid; and so forth. Artists have often endeavored to tell common stories in novel ways; Lavater certainly fulfills this promise.

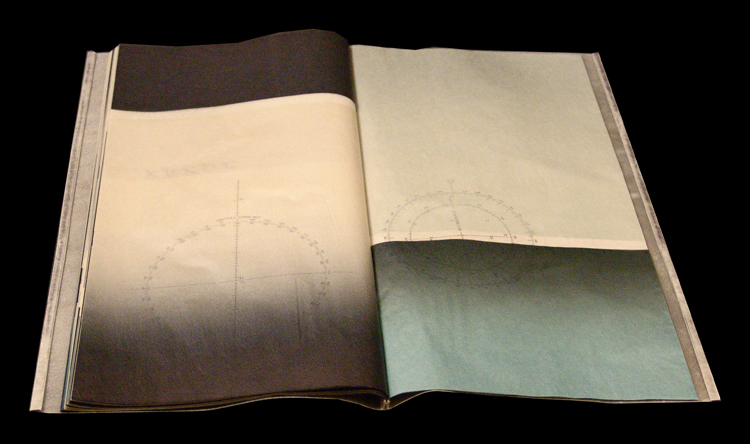

“26°57, 3’N, 142°16, 8’E” by Veronika Schäpers

Colloquially called “The Squid Book,” the actual title of Schäpers’ beguiling artist book refers to coordinates in the Northwestern Pacific Ocean where a Japanese marine biologist took the first pictures of a giant squid in its natural habitat. The only text in “26°57, 3’N, 142°16, 8’E” consists of three German poems by Durs Grünbein, while opaque maps and fading nautical images take up additional printed real estate. To flip the “pages” is to move delicate tissue paper that “sings” when you turn them, in the words of one of analysis of the book.

“Blood on Blood” by Mare Blocker

Presented in a spiral-bound photo album and printed in an edition of just 36 copies, Blocker’s title refers to family ties, and is indeed mocked up to resemble an authentic photo album. But the square and rectangular black-and-white images contained inside are actually linocuts created by the artist, printed in black on white paper and depicting people and scenes from her family history. The artist has said that she spent “20 years mining my loved ones for material for my work,” which is what most writers do, consciously or unconsciously; Blocker acknowledges this debt with good humor.

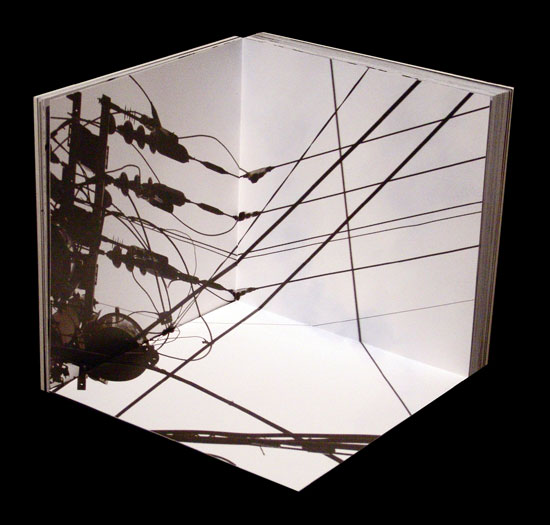

“Line” by Yoon Woong

There are no words in Woong’s 2007 book of photographs, a 6-inch square object small enough to fit comfortably in many pant pockets. Its pages open in a boxlike form, with two “walls” and a floor. The artist’s images fill the space, and focus very much on lines—whether from telephone wires or marsh grasses or Buddhist temples or semi-obscured train tracks. As is the case in many of the cleverest and most ingenious “books” in the Jaffe Collection, readers become participants in its construction, with the “story” only coming to pass through their actions in opening each “page” in its multidimensional form.

“Working Philosophy (Volume 1)” by Melissa Jay Craig

There is nothing at all to read, or even to flip, in this sculpture, which pairs the 1930 Cranach Press edition of “Hamlet” with the artist’s own 3-foot-tall fiber creation—a kind of mini-book, and like its full-size cousin, bound but fraying to the point of illegibility. Craig’s totem was one of the first objects in the Jaffe Collection that truly tested and expanded the definition of “bookness” at the heart of this extraordinary library. Equating books with the trees pulverized to make them, “Working Philosophy (Volume 1)” evokes a kind of eternally frozen decay, and is more deeply moving than it initially appears. When the late Arthur Jaffe, founder of his namesake collection, first laid eyes on the sculpture in a gallery in Pennsylvania, he likened it to the “love at first sight” upon gazing at his soon-to-be first wife from across a room.

This Web Extra is from the November/December 2025 issue of Boca magazine. For more like this, click here to subscribe to the magazine.