As of this writing in late June, the 2024 Atlantic hurricane season has already begun to burble and brew, with Tropical Storm Alberto deluging Texas. Hurricane analysts say this is just the overture to what is projected to be an abnormally busy season for major weather events.

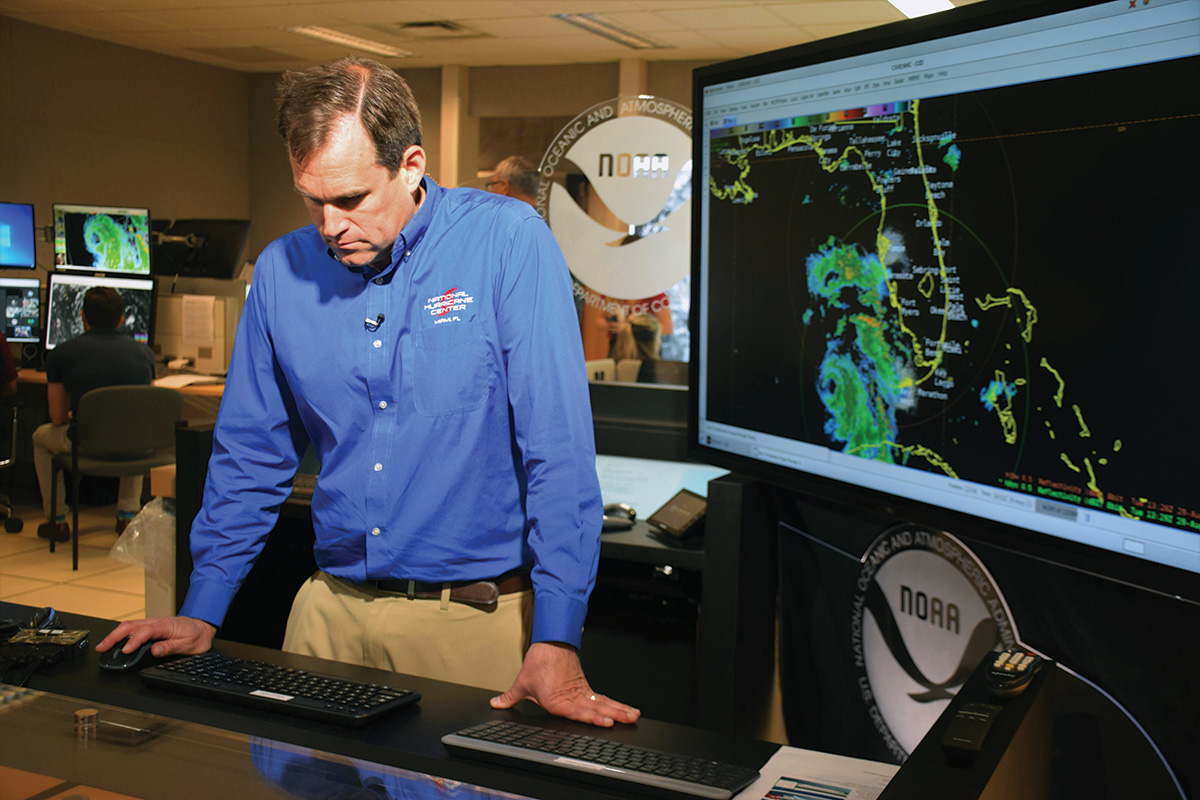

How will it affect South Florida? We can’t be certain, but Michael J. Brennan is on call, ready and waiting from his vital post as director of the National Hurricane Center in Miami. We spoke with Brennan at length for the July-August issue of Boca magazine. Here are more of his insights, exclusive to bocamag.com.

On information overload when a storm is coming

There’s certainly a lot of information out there. We have model plots posted, we have people speculating. … You’ll start to see hype and information build about a potential storm more than a week in advance, before anything is even trackable to start following. And that’s challenging, because while we want people to be aware of the risk … you also don’t want people to be alarmed or be anxious for no reason far in advance of a potential event, when there’s little that they can do to take action to prepare.

So it’s a fine line from providing lead time that’s actionable but also not going overboard in terms of speculation and information that’s really highly uncertain beyond five to seven days into the future. We really have limited availability to tell people where a storm might be. Our forecasts publicly go up to five days. We’re experimenting going out to seven days. But even at six and seven, there is a tremendous amount of uncertainty as to where a storm might be—hundreds of miles of uncertainty. So it’s really important that your readers find their trusted sources of information before the hurricane season.

On the link between climate change and increasingly destructive storms

That connection is actually one of the weaker and more uncertain ones in terms of storm intensity. The state of the science right now suggests that the strongest hurricanes could get a little bit stronger in future climate scenarios, maybe by a few percent in terms of their peak wind speed. But right now, that would almost be in the uncertainty range of our own analysis.

What we are very confident in is that the water hazards are getting worse, and will continue to worsen in future climate scenarios. So we know sea level is rising, for one. We’re observing that now. And that is going to increase the risk of storm surge inundation in places. It’s also going to expose some areas to storm surge inundation that weren’t previously exposed to it, because your base sea level is going to be that much higher now, and when a hurricane happens on top of it, you’re starting from a higher base water level.

The other thing we’re seeing and that we’re also expecting to worsen in a warming climate scenario is that rainfall rates are increasing. In hurricanes and in other weather events, warm air holds more moisture. So we’re seeing higher rainfall totals, but more critically higher rainfall rates, because that’s what really drives flash flooding and urban flooding that we tend to see in Southeast Florida.

That’s important, because water is what kills most people in hurricanes—especially freshwater flooding in the last 10 years; it’s been responsible for more than 60 percent of the fatalities. But storm surge, as in Ian, still has the potential to kill a large number of people on a given day or a given hurricane event. So we are more confident that those two hazards in particular are going to worsen in warming climate scenarios. You can see that in Southeast Florida with the sea level rise impacts, and the increase in sunny-day high-tide flooding across multiple areas. So we’re living that every day. But when you put a storm on top of that, that can be important.

On his most memorable hurricane season

I think the 2017 hurricane season sticks out in my mind as a very impactful year. It was the first time we had a major hurricane landfall in the United States in 12 years, and we had multiple major hurricane landfalls. So anytime you have these events—like you think of Hurricane Harvey, and the catastrophic flooding that played out in the metro Houston area from heavy rainfall; you think of Irma and the devastation it caused in the Caribbean and then in Florida; Hurricane Maria and how it caused catastrophic impacts in Puerto Rico. Every event has its own character and leaves an indelible impression on you as a forecaster.

Every storm here, we carry those memories and those impacts with us into the future. And while they are hard to deal with from a psychological perspective—you hate to see the suffering and the impacts—they do carry lessons that you can help apply to improve messaging and forecasting and communication of that information going forward. So we learn something from every storm. It’s not always applicable to every other storm in the future, but you do take lessons away from every event.

And one of the things that’s changed here is we’ve gotten a lot more aggressive in getting rapid intensification forecasts. Those are simply forecasts that we would not have been able to make five or 10 years ago. So now that we have a storm like an Ian or like an Idalia, where we have guidance and confidence that a storm is going to rapidly strengthen, we’re able to tell people that, hey, this system that doesn’t even exist right now, or is a very weak tropical depression, we’re expecting it to be a major hurricane in two or three days. Those are the kinds of impacts you need to prepare for.

On how storms are named

There are six lists, one for each year, in a six-year rotation in the Atlantic, and then we also have lists in the eastern Pacific. So through the World Meteorological Association Region IV, which encompasses North America, Central America and the Caribbean, we have a hurricane committee, where all the countries come together and we meet. And that committee decides how to adjudicate changes to the name list. So at the meeting, we decided as a group to retire two storms from last year’s name list in the eastern Pacific, Otis and Dora. The country affected by them suggests or proposes that the name be retired. The committee votes on it, and then votes on replacing the names.

The names alternate male and female names, and we also try to be representative of the cultural diversity within the region. With Region IV in particular, we have English and Spanish and French names on the list, to reflect the countries that are affected in the region.

This Web Extra is from the July/August 2024 issue of Boca magazine. For more like this, click here to subscribe to the magazine.