We’re supposed to accept that Andy Warhol died on Feb. 22, 1987, nearly three decades ago to the day. Like Elvis and Tupac, I’d rather not believe it. Though he hasn’t been spotted around the Manhattan haunts of his artistic primacy, his presence is felt everywhere, his legacy only deepening with time. From commercial galleries to museum shows to cinema retrospectives to magazine articles, neither Andy Warhol nor “Andy Warhol”—neither the man nor his cultivated public image—has ever gone away.

His corpus as well as his influence looms so large over both cultural and art history that it’s virtually uncontainable within one retrospective exhibition. The Boca Raton Museum of Art seems to have understood this, programming not one but three Warhol-centered exhibitions in its ground-floor galleries, a multifaceted celebration timed to coincide with art-fair season. The three exhibitions—“Warhol on Vinyl,” “Warhol Prints From the Collection of Marc Bell” and “In and Out With Andy”—each speak to a different aspect of Warhol, and each one offers an equally valid starting point with which to immerse yourself in his life and art.

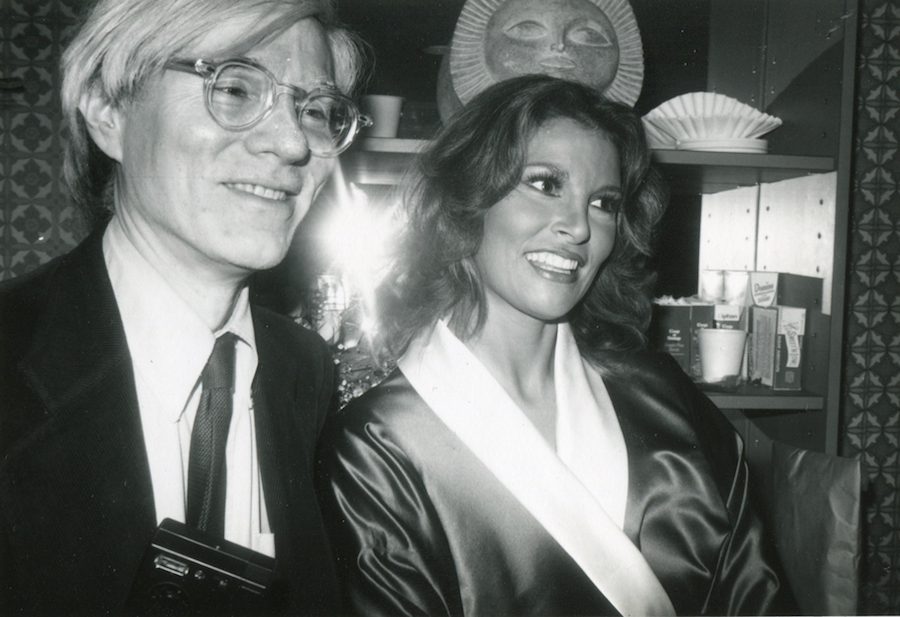

I started with Andy the person. “In and Out With Andy” is a collection of black-and-white images shot by Bob Colacello, the official photographer for Warhol’s Interview magazine. Few had Colacello’s access to the Factory and the social parties Warhol attended with his celebrity friends, and few would have seemed less star-struck by the company than Colacello, who called himself an “accidental photographer.” His untrained eye and lack of deference for his subjects result in candid, off-kilter images of Warhol himself—munching on a scone in Naples one morning—and his endless entourage.

Shooting on a pocket-sized 35mm camera and lingering unobtrusively in doorways and outside windows, Colacello captured Kevin Farley’s naked midsection, Fred Hughes bare-assed in front of a bathroom mirror, and Roman Polanski sporting the glassy-eyed looked off the heavily drugged. Warhol appears demystified in many of these shots; in most of them, he’s a social butterfly and all smiles, without the disaffected cool he projected when he knew was being filmed.

But the most importance aspect of “In and Out” is its revelation of the depth and breadth of Warhol’s Rolodex. We expect to see Mick Jagger and Jerry Hall, but not so much Arnold Schwarzenegger and members of the Reagan Administration. It’s surreal to imagine Henry Kissinger and Paul Morrissey cavorting at the same party, but Warhol made no distinctions. Fame was all that mattered, whether you were a country singer or a countess—a philosophy that certainly imbued his artwork.

Though Warhol’s oeuvre encompassed painting, printmaking, sculpture, film and even shoe illustrations, the Boca Museum recognizes that only one medium proved to be a consistent Warhol muse from his early days as a commercial illustrator to his death: album art. “Warhol on Vinyl” is a fascinating overview of an artist’s radical evolution as filtered through a chronological progression of identically sized 12-inch square canvases. It’s also a reminder of an art form our culture risks losing, as music consumption has (d)evolved from physical to digital collections.

Warhol’s contributions to album art began way back in 1949, during his time as a commercial illustrator. These commissioned blotted line drawings for classical, jazz and ethnic folk records bear little resemblance to the signature style he would develop later. Most of them supplemented barebones text-driven covers with a drawing of an instrument; a Spanish-language instruction LP included a trio of sombreros.

By 1954, however, you can see his imagination begin to flourish, with his graphically bold Thelonious Monk image—the word “Monk” fills the cover, each letter jutting at a jazzy angle. In 1955, his cover for a Count Basie album, with the Count looking askance as a cigarette dangles from his lips, made history as Warhol’s first celebrity portrait. Viewers will detect the embryonic form of his repetitive serial paintings—one image repeated in multiple hues—in his different-colored editions of Kenny Burrell’s “Blue Light.”

His unfettered brilliance fully flowered in the ‘60s and ‘70s, when he released a number of covers that were as interactive as they were innovative, breaking new ground that few, if any, album artists have managed to replicate since. Every music lover knows his iconic “Banana” cover for his protégés the Velvet Underground, but comparatively few have peeled back the banana to reveal the pink phallus underneath—a naughty treat for the lucky owners of the original edition.

Soon after, he would create a functional zipper on the Rolling Stones’ appropriately lascivious cover for “Sticky Fingers,” with its close-up of a jeaned crotch: Pull down the zipper and you could see the underwear. For John Cale’s “Academy in Peril,” Warhol filled the cover with serial Kodachrome portraits of the singer-songwriter, which consumers of the album could cover up or reveal. Warhol didn’t just make attractive artwork that spoke to the bands’ sensibilities: He revolutionized an art form, turning album covers into movable sculptures.

Finally, “Warhol Prints From the Collection of Marc Bell” is a greatest-hits collections with which to send Warhol-ites homem as satisfied as ever by the breathtaking familiarity—the 20 variations of Campbell’s Soup Cans, the rainbow of Maos, the neon moonwalkers. It’s a cliché to re-iterate the obvious, but seeing these images out of context or on calendars or on websites hardly does them justice. Nobody—at least since Van Gogh—saw flowers like Warhol did, in all their psychedelic radioactive strangeness, and his “Flowers” series packs the most fragrant wallop when hung on a gallery wall in large frames. Equally stunning is his quartet of Queen Elizabeths, all the same but different, both honorable and disconcerting to the monarch, equal parts a tribute and freakshow.

Bell’s collection includes Warhol’s ahead-of-his-time “Ads” series from 1985, which not only revealed the artistic beauty in the corporate logos of Chanel, Paramount, Macintosh and others. It also captured the ubiquity of corporate branding in our everyday lives and shattered the distinctions between high and low art. The “Myths” series, from 1981, which hangs adjacent to “Ads,” delivers a similar message, elevating figures from popular culture into Warhol’s populist aesthetic: Superman, Dracula, Mickey Mouse, Santa Claus.

But who’s that in the bottom right corner? It’s Warhol himself. Ever the self-reflexive re-appropriator, he was probably the first to receive the wisdom that three-plus decades of art history and analysis have posthumously concluded: That he has become as mythic as his subjects.

All exhibitions run through May 1 at Boca Raton Museum of Art, 501 Plaza Real, Boca Raton. Admission costs $12 for adults, $10 for seniors and free for students with ID. Call 561/392-2500 or visit bocamuseum.org.