Boca Raton has done a lot of growing up in the last 100 years, from its days as a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it farming town to resort playground, Silicon Beach tech hub, and now to a force to be reckoned with in business, housing and education.

Photos courtesy of the Schmidt Boca Raton History Museum and Morikami Museum and Japanese Gardens

The Pioneer Era

While you won’t find his name on any local streets or buildings, the city of Boca Raton owes its founding to the pioneering spirit of one Thomas Rickards.

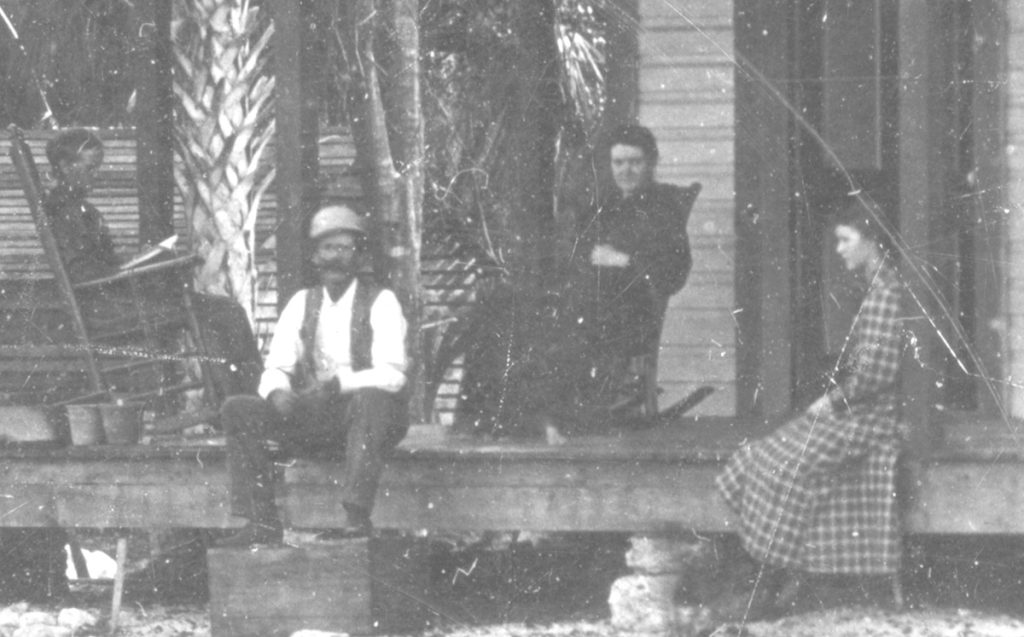

Born in Ohio in 1845, Rickards moved to Florida for the same reason as most of us—to never endure another winter. After spending some time in Gainesville, Rickards found work as a surveyor for Henry Flagler’s Florida East Coast Railway (FECR) at a time when the railroad was extending south from West Palm Beach to Miami. Rickards’ work with the FECR brought him to the area that is now Boca Raton, where he surveyed and platted the land for the railroad. By 1896, Rickards had platted out the entire town and began to sell land to fellow pioneers seeking fortune.

By 1904, Rickards was a full-time Boca resident, building a home of driftwood south of what is now the Palmetto Park Bridge. Like most early Boca pioneers, Rickards grew citrus on his land. As an agent of the Florida East Coast Railway, Rickards facilitated the establishment of Boca’s first settlement, the Yamato Colony, named after the Japanese word that translates to “the whole of Japan.” A letter from Yamato Colony founder Joseph Sakai to Rickards reveals the excitement with which early pioneers viewed Boca Raton: “I am still living under dusty air of New York with dreaming (sic) my future house in Fla,” writes Sakai.

Early settlers of the Yamato Colony enjoyed success as farmers growing winter fruits—mostly pineapple—that they shipped to northern markets and back home to Tokyo. Despite many flourishing years, however, the population of the Yamato Colony began to decline during the Florida land boom of the 1920s when farmers sold their plots at a premium and left the state. Those that remained eventually had their land taken by the federal government in the 1940s through eminent domain to build an Army Air Corps training center.

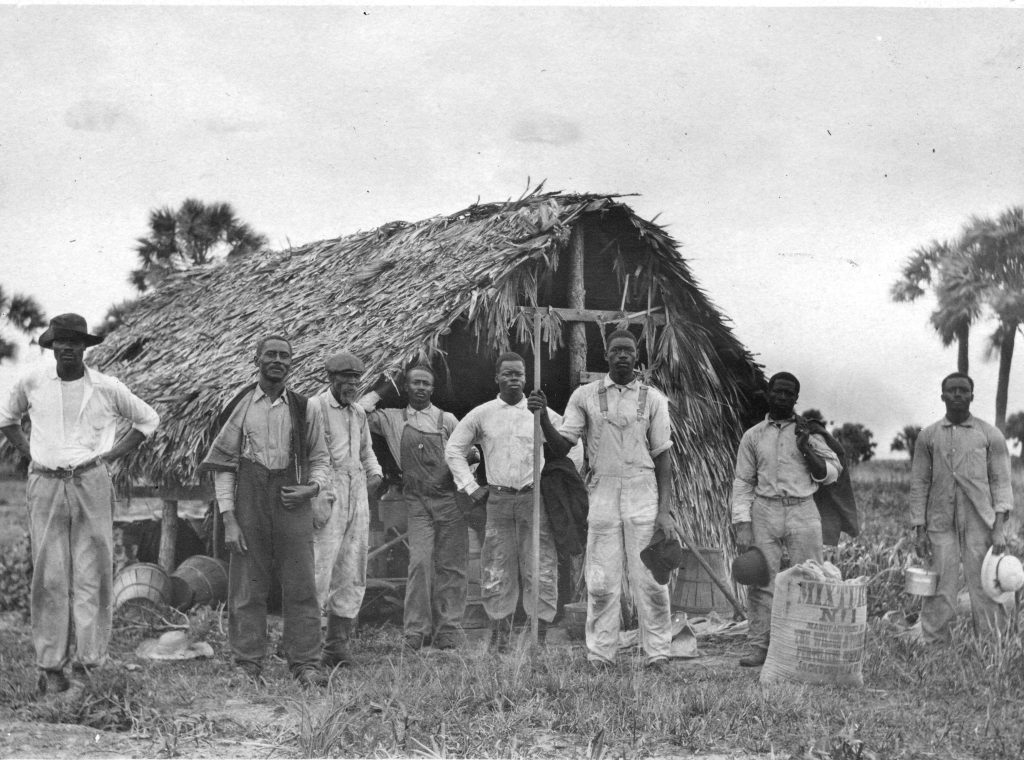

The work of early Boca pioneers helped develop the infrastructure of agriculture that would eventually attract Black southerners and Bahamians to the area where they would establish the city’s first neighborhood, Pearl City. Founded in 1915, Pearl City was a home to day laborers who worked on the area’s citrus and bean farms. Today, Pearl City remains the city’s oldest community and was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2023.

The remnants of Boca’s pioneer days remain with us, such as Yamato Road being named after the first settlement, as well as the Morikami Museum and Japanese Gardens, which was founded by original Yamato settler George Morikami. This era also set the stage for the next chapter of Boca Raton, one that established the city’s reputation for luxury and leisure.

The Resort Era

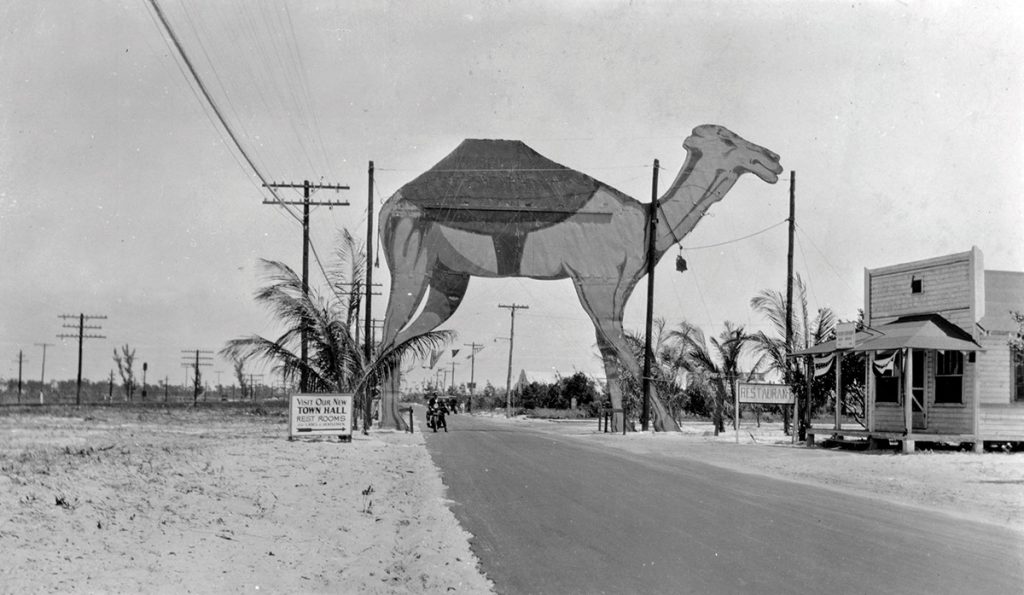

As Cynthia Thuma wrote in her book Images of “America: Boca Raton,” the city “has always been about doers and dreamers, entrepreneurs and philanthropists, movers and shakers.” Architect Addison Mizner, a California gadfly who moved to the city in its centennial year of 1925, at age 53, fulfilled most if not all of these descriptors. Boca Raton named Mizner its first city planner, and he immediately set out to transform a largely agricultural region into the “Venice of the Atlantic.”

Buoyed by the Florida land boom, these were heady times in Boca. Ostentatious ads compared Florida real estate to the California Gold Rush, and lauded “Boca Raton: Where Promises Are as Good as the God-Given Soil.” Mizner’s ambitions involved a 1,000-room hotel with two golf courses, a polo field, parks and miles of landscaped streets. In a move worthy of William Randolph Hearst, he intended to build “Castle Mizner” for himself on Lake Boca Raton, complete with a drawbridge and four-story tower.

These blueprints never came to fruition: The land boom, which promised bottomless development and prosperity in the early ‘20s, fizzled by 1927 thanks to a confluence of factors, from the devastating effects of the Miami Hurricane of 1926 to rail embargoes on building supplies to reports from northern visitors perturbed by the region’s sand flies, mosquitoes and humidity.

But the buildings Mizner did complete, mostly in his signature Mediterranean Revival style, would define the burgeoning city’s urbane aesthetic. He built the neighborhoods of Old Floresta and Spanish Village to house his employees. His Administration Building, modeled after artist El Greco’s home in Spain, would house the city’s first restaurant, and stands today as The Addison event venue. And he completed the 100-room Ritz-Carlton Cloister Inn, which opened in 1926 and which would evolve into the Boca Raton Resort & Club and now The Boca Raton.

The Cloister’s elevation toward the grande dame of Boca resorts occurred under the ownership of Clarence H. Geist, a financier with an ego to match Mizner’s, and a similar appreciation for European design. After buying out Mizner’s $7 million debt, Geist hired acclaimed architectural firm Schultze & Weaver to extend the Cloister, opening his expanded and renamed Boca Raton Club in 1930. Highlights included a courtyard with Persian-styled water channels, tiled walkways and fountains; and the opulent Cathedral Room, with gold-leafed columns, coffered ceilings and giant Venetian chandeliers. (On a more practical note, Geist also funded the city’s first water plant.) Boca’s first clubs for women, polo and hunting grew out of the resort, propelled by its upper-crust winter visitors.

Outside of this pocket of luxury, Boca remained an agricultural community. In 1933, August H. Butts took advantage of the land bust to buy farmland cheaply, establishing a major bean farm and employing 400 in his fields. Construction contractor Louis Zimmerman and his wife Lola fed the growing population at Palms Café, and in 1934, a year after the repeal of Prohibition, they opened Zim’s Bar, Boca’s first watering hole.

Boca Raton faced the same Depression-era economic uncertainty, racial and class divisions, and wartime anxiety as the rest of the country. Toward the end of the 1930s, Boca Raton’s influential fourth mayor, Jonas Cleveland Mitchell (whose name emblazons one of our elementary schools) traveled to Washington, D.C. to lobby for a military base in Boca Raton—a move that would transform the city once again.

The War/Postwar Era

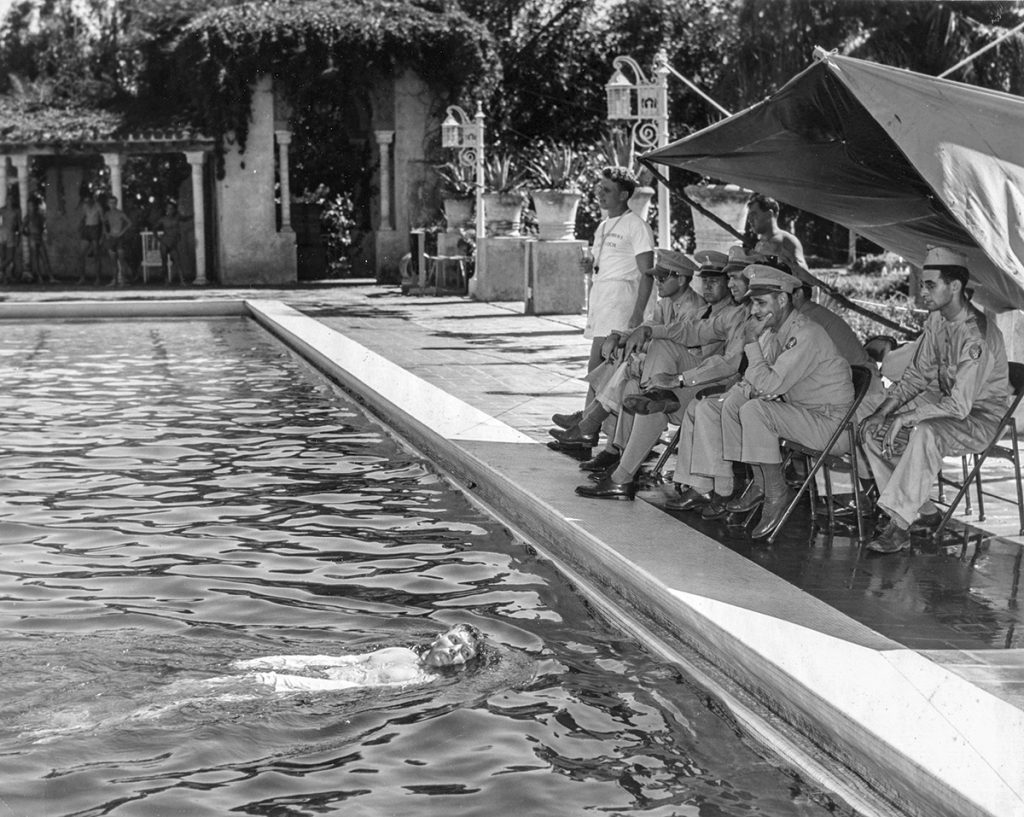

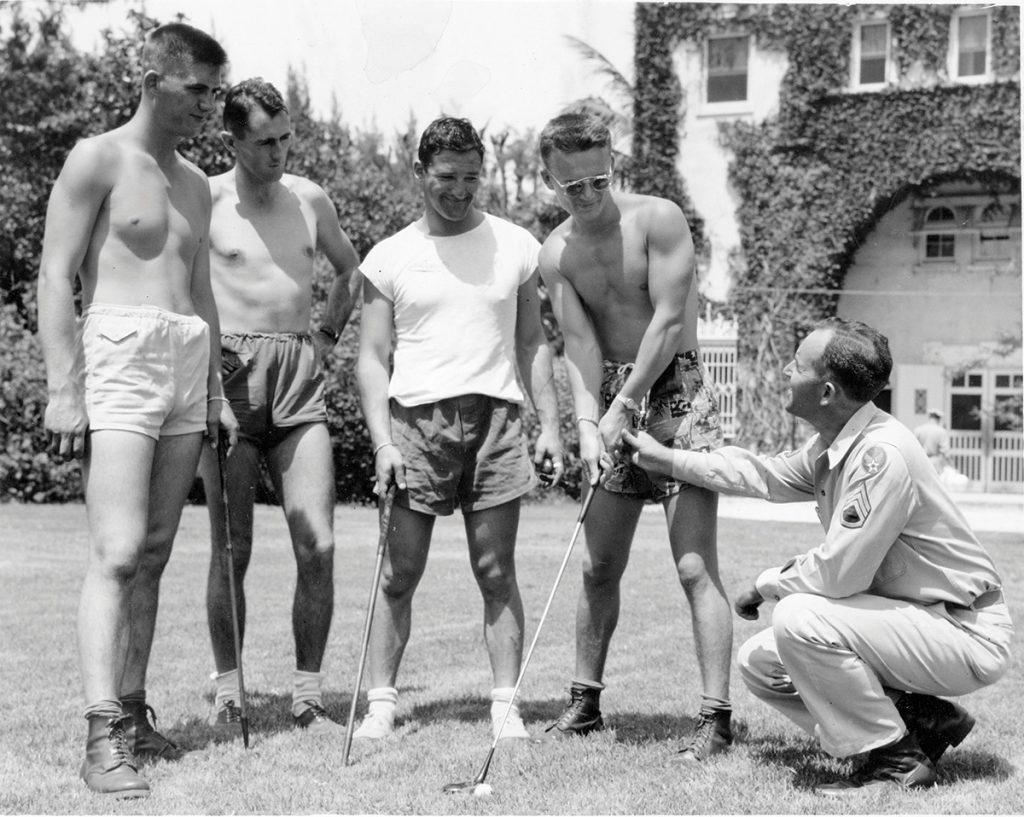

When the U.S. entered World War II in December 1941, Americans’ lives were changed in an instant. Boca Raton was no different. The Army Air Corps relocated its radar training technical school from Illinois to Boca Raton—the town was ideal since it already had a small airport and two railroad lines—and servicemembers underwent top secret training sessions. They couldn’t take notes during class, were sworn to secrecy, and could even be court-martialed if they said the word “radar.” Black soldiers were at the base but were trained and housed separately due to segregation; about 28 of them would become part of the storied Tuskegee Airmen.

With a population of just 750 people, it seemed overnight that Boca Raton was overrun with servicemen and women; over the course of the war, up to about 100,000 servicemembers were in Boca Raton. Every room and house in town was rented out, and even the Boca Raton Club (now The Boca Raton) gave up its property for military use. Eight bunk beds were put into each hotel suite, and during training, the resort’s golf course was pockmarked with pup tents and foxholes. After the Allies’ win in 1945, the Boca Raton Air Field continued its work until a hurricane smashed through the town in 1947. It was downgraded to an auxiliary Air Force base until 1959; by then, the town had purchased 2,400 acres of the property to be transformed into Florida Atlantic University and the Boca Raton Airport. It’s said that visitors can still see markings from the runways in the school parking lots, a small reminder of Boca Raton’s impact on the outcome of the war.

Now that war was in the rearview mirror, Boca Raton could shift its focus to growth. The women of the Boca Raton Christian and Civic Club were astonished to find that 1,000 people attended a small art exhibit they hosted, which led to the founding of the Art Guild of Boca Raton in 1950. Thanks to a $6,000 parcel donation from Ada MacKidd, a museum was built, continually expanded, and eventually became the Boca Raton Museum of Art.

All around Boca, construction was abuzz. Arthur Vining Davis bought the Boca Raton Hotel & Club, and his real estate development company, ARVIDA, upped the ante on Boca’s growth. The Boca Raton Chamber of Commerce was established in 1952, the Royal Palm Yacht and Country Club opened its doors in 1959, and Marymount College was founded by nuns (and later renamed Lynn University) in 1962.

Tragedy struck the town in 1967, though, when Randy, 3, and Debbie, 9, Drummond died after drinking milk poisoned with enough arsenic to “wipe out the entire city.” It took an hour to get to the closest hospital, blood tests had to be driven to Miami, and both children died. Their mother, Gloria Drummond, immediately started fundraising to build a Boca Raton hospital and tossed the first shovelful of soil at the ground-breaking in 1965. Today, Boca Raton Regional Hospital is in the midst of a major fundraising campaign, so far netting almost $290 million.

The Tech Era

After World War II, Boca Raton was no longer just a vacation destination for the rich and powerful. The city experienced an—at the time—unprecedented population boom, jumping from 992 in 1950 to 6,961 in 1960. And it wasn’t just new residents that Boca was attracting, either. Florida’s appealing tax policies, low housing costs and tireless lobbying from the newly formed Boca Raton Chamber of Commerce in 1952 made the city an enviable destination for big business. And in 1967, Boca became home to one of the most significant business titans of the time—IBM.

By the 1960s, IBM was the largest manufacturer of computers in the country. The tech giant needed more manufacturing centers to reach the ever-increasing demand, and so purchased 550 acres of land west of I-95 to construct what would become a sprawling campus. Designed by famed architect Marcel Breuer, the campus was described in a 1983 issue of PC Magazine as having “the solid, impenetrable aura of the Pentagon.” It was at this campus that IBM would develop a product that would forever revolutionize computing.

In 1981, IBM launched the first-ever personal computer that set a new industry standard. Demand for the IBM 5150—code-named the “Acorn”—exceeded even the loftiest of expectations, with 500,000 machines sold within 18 months of its release. TIME magazine named it “Machine of the Year,” the first time such an honor was given. As demand for the Acorn skyrocketed, IBM added more personnel to its Boca campus, with a staff that grew to more than 10,000. Soon, more tech firms began flocking to Boca, earning the city the nickname of “Silicon Beach.”

The aforementioned PC Magazine article reads, “Before IBM, all that Boca Raton had to brag about was a playboy’s fantasy of the ultimate luxury resort: the Boca Hotel & Club.”

The IBM era of Boca came to an end when the company restructured in the 1990s, moving hardware manufacturing from Boca Raton to Raleigh, North Carolina. Since 1996, the campus has been bought and sold several times over, until eventually being redeveloped into Boca Raton Innovation Campus. And like the former IBM campus, the city itself has changed just as much with the times.

The New Boca Era

By the late 1980s, the business, education and residential booms spurred by IBM, FAU and ARVIDA had nonetheless failed to generate an attractive downtown, which contained all of 73 housing units and the lowest office rents in the county. The site of today’s Mizner Park epitomized the struggle. The address’ previous tenant, the conventional indoor shopping center Boca Mall, closed in 1989, having long shed its most esteemed retailers, Britts and Jefferson Ward. By this time, the mall was a husk of its early ‘70s glory, with one resident reducing it to “a big blimp hangar.” Its final holdout, the Dive Bar saloon, may have inspired the colloquialism “dive bar.”

Within just two years, Mizner Park had risen like Lazarus from this undesirable bit of real estate, opening in 1991. As with many a project of its size, scale and cost, the development was not without controversy. Locals voiced their concerns about parking, traffic and the hefty price tag: $68 million in bond money approved by the city council, plus $50 million in infrastructure improvements. Now, of course, Boca Raton is inconceivable without this mixed-use anchor.

Cultural advancements soon followed. The International Museum of Cartoon Art, a $10 million collection advanced by “Beetle Bailey” creator Mort Walker, operated in Mizner Park from 1992 to 2002. The Boca Raton Museum of Art opened its 44,000-square-foot anchor facility in Mizner Park in 2001. Royal Palm Place broke ground in 2002, and the Boca Raton YMCA followed suit in 2003.

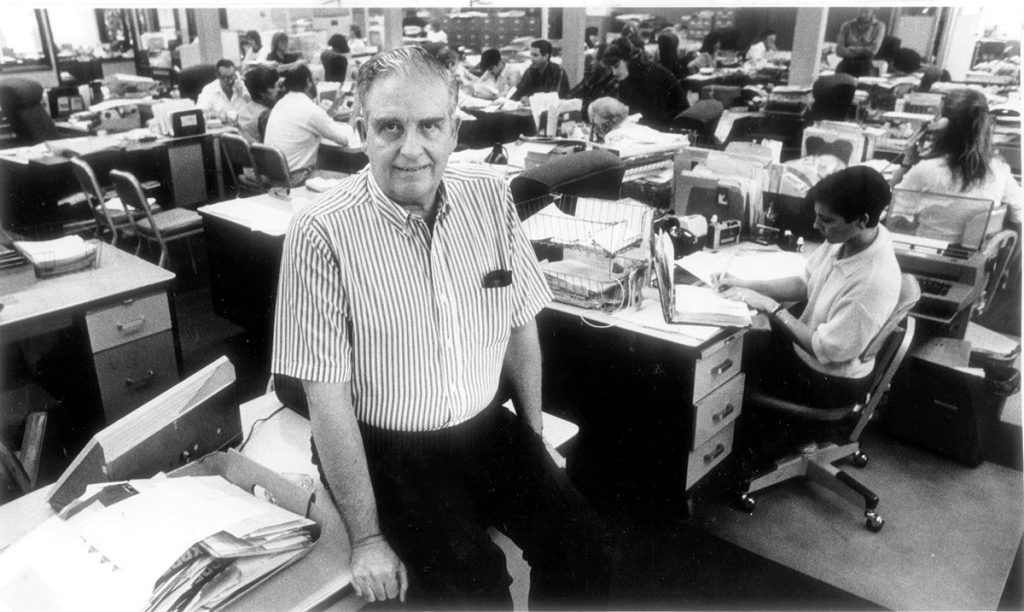

Boca Raton did not always make news for the right reasons in the modern era. In 2001, a week after 9-11, American Media, Inc., which published the National Enquirer out of Boca, was one of five national news organizations to receive an anthrax-laced letter in a series of bioterrorist attacks identified by the FBI as Amerithrax. An AMI photo editor, Bob Stevens, opened the missive and inhaled the toxin, becoming the first known casualty of the attacks. Six years later, three people were murdered, and two more were abducted, in a chain of crimes at Town Center mall that remain unsolved.

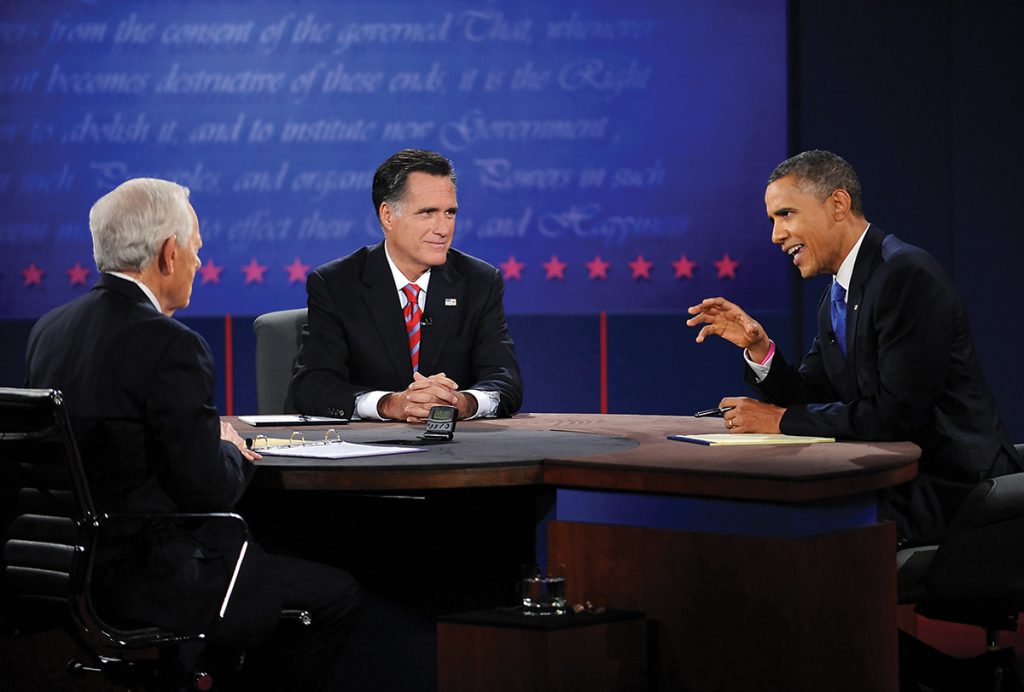

Mostly, though, progress has continued apace during the twilight of our centenary. Lynn University hosted a presidential debate in 2012, and our downtown has continued to develop. In 2023, Boca shocked the world of NCAA basketball when FAU’s men’s team made it all the way to the Final Four. The Boca Raton resort, the institution that put Boca on the map, will celebrate its own centennial next year. For this property, and the city that sprouted around it, the best may well be yet to come.

This story is from the May/June 2025 issue of Boca magazine. For more like this, click here to subscribe to the magazine.