From scaling Kilimanjaro to running the Boston Marathon and diving into ocean depths on a single breath of air, local athletes have met some of the fitness world’s most daunting challenges. Learn how they pushed their limits to meet the moment.

Written by Tyler Childress and John Thomason

Making the Climb

Drs. Ari Silverstein and David Taub

Summiting the snowy peak of Mount Kilimanjaro was an ascent 30 years in the making for Lynn Cancer Institute’s Dr. Ari Silverstein. The famed Tanzanian volcano left its indelible first impression on Silverstein during a safari he took with his family to Kenya in his 20s. “You’re in the middle of nowhere in the plains of Africa, and there’s this giant mountain,” recalls Silverstein. “I asked, ‘Can we hike that?’ And they said, ‘You can, but it’s a lot bigger than it looks.’”

Silverstein left Kenya resolved to one day return and make the climb, so last year, when longtime friend and fellow Lynn Cancer Institute Dr. David Taub came to him and said that he wanted to scale Kilimanjaro for his 50th birthday, Silverstein jumped at the opportunity.

“At this stage of life, where the kids are grown and professionally successful, I [was] looking for a challenge or something to kind of sink my teeth into,” says Taub. Silverstein adds, “He said, ‘I’ve been thinking about this for a couple years,’ and [I said] enough thought. Let’s go, let’s do it.”

The duo spent the following few months researching the right outfitter to guide them on their trek while training for the 20,000-foot ascent. With little options for practice in the nation’s flattest state, the doctors visited Florida Atlantic University’s Flagler Credit Union Stadium several times a week to climb up and down the stairs while strapped with 20-pound backpacks.

A month before they were set to fly to Tanzania, they put their training to the test with a hike up one of Colorado’s 14,000-foot peaks, a weekend excursion which nearly put an early end to their ambitions. As the doctors ascended the Colorado mountain, Taub was assailed by coughing fits from the lack of oxygen while Silverstein began to question the green light his cardiologist had given him after putting in a heart stent just one week prior. “For me to get to 14,000 feet was just like, ‘Am I going to have a heart attack and die on the spot?’” says Silverstein.

Fortunately, the pair reached the peak and made it back down without incident and were back at work Monday morning. For the doctors, the trip served as proof of concept that they could climb Kilimanjaro. They discovered a month later, however, that Kilimanjaro is far less forgiving than a Colorado mountain.

“The daily hikes were about six or seven hours, eight or nine miles, up a couple thousand feet, down a couple thousand feet,” says Silverstein, with the ups and downs intended to acclimate the body to the increasing altitudes. “The first five or six days are steady, solid days; the last day is really brutal.

“The last day, you basically climb up to about 16,000 feet, where you camp during the daytime. You make the ascent at night. They say that’s for a couple of reasons. For one, it’s so you can’t see where you’re going, because [for] a lot of people, if you see it, you would turn around. And two, so you could hit the peak at sunrise.

“That night you get up and it’s literally 0 degrees. You get dressed, you put your headlamps on, and you basically start walking straight up. … Over the next five-and-a-half hours, you’re walking up 4,000 feet, freezing cold, you sort of can’t see, there’s a lot of other people ascending, some ahead of you, some behind you, and you can basically see this little trail of headlamps but you can’t really tell the distances, and really you’re just looking at the feet of the person ahead of you and trying to keep going. … Meanwhile, your heart rate—because there’s no oxygen—is going 130 beats per minute.”

It was at this point that the doubt started creeping in.

“At one point I was having some difficulty breathing, and I was like, ‘Oh man, I brought all these guys out here, I don’t want to be the guy who holds them back or doesn’t make it up,’” says Taub.

After a dogged approach, the group summited the peak just in time to watch the sun rise. “You’re on top of the world; it’s incredible,” recalls Taub. The group spent about a half hour taking pictures and celebrating, thinking that the hardest part was behind them.

“The ascent was really hard,” says Silverstein. “It was physically and mentally demanding. Getting down, which you think is easy, is just brutal … You’re just banging on your knees for basically 15 hours. It’s not hard, it’s just miserable.”

Finally, after a 10-hour descent, the group arrived at the base, where they could finally revel in their accomplishment over a celebratory drink. “It’s exhilarating to work really hard for something, train and train, and actually achieve a goal,” says Silverstein.

“It was a true adventure,” says Taub. “Not just physical, but a journey that we all took together that I think we’ll probably never forget.”

Staying the Course

Melissa Perlman

For Melissa Perlman, the journey to the starting line of the Boston Marathon begins five months before the race. It’s then that the Delray Beach public relations professional begins her rigorous training regimen—running 70, then 80 miles a week, often back and forth across the Linton Boulevard bridge, or on treadmills with the incline function turned way up, to simulate, amid the flatness of Florida, the famously hilly conditions of the Boston terrain.

“The buildup for Boston was my most intense buildup to date,” she says, referring to her fourth Boston Marathon run this past April. “It’s all just preparing your body to get used to time on feet, which is huge. You’ll be out there for upwards of three hours, so you’re trying to find those stressors, as we call them, to get your body used to the 26.2-mile voyage.”

If she sounds like a longtime veteran of long distance running, it’s because Perlman, whose Instagram handle is @melrunsfast, is, indeed, a fast learner. She ran her first marathon while in her 30s, in 2018, inspired by her boyfriend’s entry into the New York City Marathon the year before. She completed her first race, Grandma’s Marathon in Duluth, Minn., at 3:09:17.

The following year, she ran her first Boston Marathon, improving on her Duluth numbers by more than nine minutes.

Six years and nine tournaments later, Perlman has continued to shave more time off her personal records, culminating in a career-best finish of 2:42:28 at the 2025 Boston Marathon, which won her eighth place among women 40-44. And she managed this feat while racing in the elite division for the first time, earning her laudatory coverage in Runner’s World magazine under the headline “Melissa Perlman is the Feel-Good Story of This Year’s Boston Marathon Pro Field.”

“The coolest part for me of the entire race is that my bib said ‘Perlman,’” she recalls. “When you’re in the elite or professional field, your last name is on your bib. People don’t know the difference between me and real professional runners that they see on TV all the time. They just see someone running in the field up front, with their last name on their bib, and that was just the most incredible experience to have—thousands of people for 26 miles-plus yelling your name and cheering for you. They pretend they know you, like, ‘Perlman, you got this.’ And ‘keep going, keep fighting.’ … I spent a lot of that race just smiling at people.”

For Perlman, the encouragement fueled her when she needed it most—during the marathon’s notorious hills, from the Charles River crossing through Heartbreak Hill, whose difficulty often forces novice runners into a walking pace. “You get to mile 16, 17, 18, 19, and there’s four massive hills that you have to get over,” she says. “That’s when it started to really hurt, but you train for that. If you’re trained, even when your legs are in pain, you’re not going to break down when you hit the wall. People talk about hitting the wall, and then all of a sudden they go from running eight minutes per mile to 12 minutes per mile—that’s hitting the wall. So, when it started to hurt for me, I went from going six minutes per mile to 6:20 per mile. So, it’s harder, and it gets to me, and I don’t have that light bounce, but you just pull from mental and physical strength to get yourself through. And then you hope when you get to mile 20, and then for the final 6.2 miles, that you can get a little bit of that bounce back.”

For Perlman, the most difficult aspect of the race was the unusual logistics of running much of the course alone, having split off from her class of 60 elite women by mile 7 or so. “You’re really having to go internally and build, create goals, play games in your head of getting to certain points. You keep pushing yourself when it’s really hard and there isn’t someone really close.”

Perlman will next set her sights on qualifying for the Olympic trials in 2028, endeavoring always to improve her personal record. She says her life on the asphalt has transformed her in many ways.

“I ran in high school; it was my identity,” she says. “And in college, when I stopped running, I lost that for a very long time. So to have that now in my life, for the last seven years or so, and to be excelling and to be winning again, and to be running my best times, it’s this full-circle feeling of loving all parts of me, of who I am and the intensity and the passion of putting my mind towards something and achieving it.

“Physically, of course, I feel stronger and better than I’ve felt in my life,” she adds. “And as a woman over 40, I think that’s an important thing, and probably inspiring for other women that are aging. We can still improve and get stronger. … But for me personally, it just makes every day fun. Outside of work and other parts of life, it really gives me something to work towards, to have a goal, a purpose in that way. And then when I get to achieve it, I love it. It’s like a celebration.”

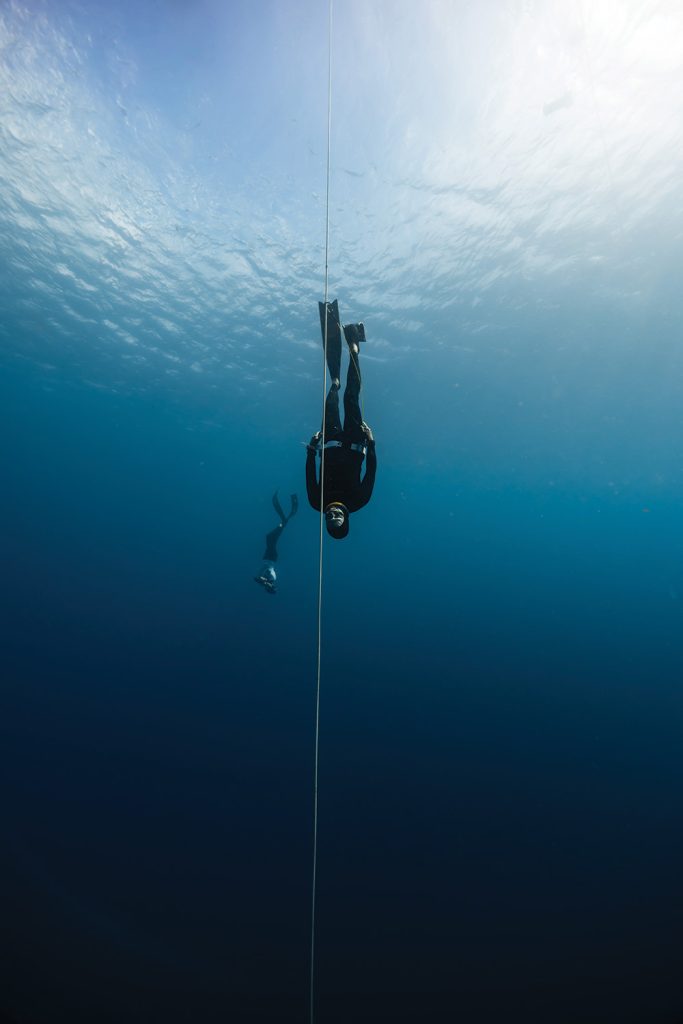

Into the Deep

Kevin McNally

Delray Beach freediver Kevin McNally’s biggest health scare occurred not in deep water but upon coming up for air. It was then, having completed his task at the 2024 CMAS Freediving World Championship in waters off Kalamata, Greece, that McNally blacked out, immediately “face-planting,” as he puts it, into the water. “I never got an answer on how long I was out,” he recalls. “But long enough for the safety divers to swim me over to the platform and pull me up onto it. Then I was put on oxygen.

“When I woke up, I was on the platform with the oxygen, a medic and a physician working on me. It took over an hour to get my oxygen saturation back into the 90s. This is because I squeezed in addition to the blackout.” “Squeezing” happens when the alveoli in the lungs rupture and start bleeding, and it’s a more serious complication than a typical resurfacing blackout, in which the competitor usually regains consciousness within a minute.

McNally is not, he stresses, a “thrill seeker. You won’t see me skydiving or on a motorcycle or even rollerblading.” And yet his sport of choice is not for the faint of heart. Competitive freediving, in which athletes dive to a predetermined depth, retrieve a piece of Velcro to prove they achieved their goal, and swim up to the surface all while holding a single breathful of air, requires rigorous training for both body and mind. Having honed a technique for breath-holding over many years—his record underwater has exceeded four minutes—McNally’s regimen includes three gym work outs a week and at least two yoga sessions.

Mentally, keeping one’s eye on the prize, so to speak, is just as important. “Once I get to the bottom, if I’m at, say, 200 feet, I don’t think to myself, ‘it sure is a long way back to the surface.’ I stay very focused on where I am. I make very small movements with my arms and my legs. I don’t do any extended reaches or looking up with my neck; any of those things can cause a severe lung injury.

“The most challenging aspect is getting acclimated to depth,” he adds. “There are no quick ways of getting deeper. Your body has to adapt to deeper and deeper water over a slow period of time. I have rushed it a couple of times and have had a couple of injuries from trying to rush things.”

McNally credits his affinity for diving to his childhood in Miami, where he would snorkel with his siblings to recover shells from the ocean floor. He embraced SCUBA diving in high school, and he discovered freediving as a discipline in the late 1990s.

But it wasn’t until 2010 that he found an instructor in West Palm Beach and took his first class in the sport. Some six years later, he graduated to advanced classes and training camps off the coasts of Mexico and the Canary Islands. “While on those trips, I met some of the really deep freedivers, and they mentioned to me that there were world records for people over 50. And they were in 10-year increments. That gave me the idea of what to do when I retired, to go after those world records.”

That retirement hobby has become all consuming for McNally, who spent 30 years in the traffic engineering business. He has competed in five competitions from AIDA International, one of the global governing bodies for freediving, and he has achieved its peak U.S. ranking of 22. He holds the No. 2 record in dynamic freediving from the U.S. Freediving Organization, for an 82-meter descent in Tampa in 2024. McNally will be 70 in January, and he will thus enter a new age group that he expects to dominate, casually stating, “I should be able to break the world records in 2026.”

Competing at this level often means revolving his life around the sport. He spoke to Delray magazine from Greece, amid a four-month stint in the country, the longest he’s ever been away from his Delray Beach home—and his long-term partner, public relations professional Elizabeth Kelley Grace. Keeping this distance, he says, is the hardest part of the life he’s chosen.

McNally’s compensation comes in the form of bragging rights. “There is no prize money,” he says. “Probably the biggest prize is a medal you can wear around your neck, and if you get a world record, your name will be on a PDF file on an obscure website that not too many people ever look at.”

With no monetary gains on the horizon, McNally thrives on his passion for the practice. “It’s a very centering sport,” he says. “You have to be very focused and able to have a clear mind and be very physically fit and be able to accept coaching from better divers. And I love being in the water and the connection to the water and my fellow freedivers. It’s a great group of people.”

This story is from the November/December 2025 issue of Delray magazine