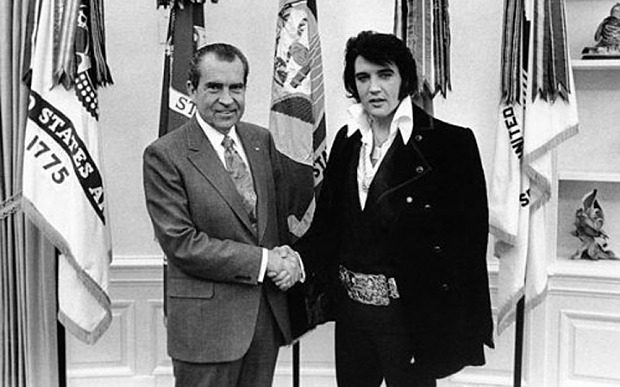

“Elvis & Nixon,” which opens today, is what happens when a feature film is adapted from a single photograph and not much else. The legendary, almost mythical image of President Nixon clasping hands with Elvis Presley in the White House in December 1970 is the only document that such a meeting took place: Nixon hadn’t yet reached his paranoid stage of recording every conversation in the Oval Office.

And, as director Liza Johnson and screenwriters Joey and Hanala Sagal and Cary Elwes reveal in their skimpy movie based on the encounter, there just isn’t enough there there. There is no dramatic thrust in this formless vanity project, and what little plot exists seems xeroxed from a Smithsonian article from 2010. The rest is fanciful tabloid fodder, a movie as inconsequential as a gossip column, the cinematic equivalent of clickbait.

But hey, at least it’s got some great actors who respect their legendary characters enough to find the human beings underneath the exaggerated public personae. Michael Shannon’s Elvis, who admittedly sounds more like Michael Shannon than Elvis, is first seen watching “Dr. Strangelove” in Graceland and shooting one of his televisions with a gold-plated gun. Fed up with his ostentatious lifestyle while the rest of the country is plunging into an abyss of war, crime and drugs, he hops a plane to Los Angeles and meets longtime friend and music executive Jerry Schilling (Alex Pettyfer), corralling him onto a flight to Washington, D.C. with the intent of meeting the president and obtaining a badge to become a “federal agent at large”—the King’s way of serving his patriotic duty by covertly busting hippies for drug possession. Elvis and Nixon, it seems, had more in common than you’d think.

It takes a little arm-twisting on behalf of the president’s staff, but eventually, the meeting does take place, with Kevin Spacey hunching his back and simulating the alopecia necessary to embody the foul-mouthed Republican. The men bond over Dr. Pepper and hating the Beatles, and they commiserate over negative press. Their underlings discuss the pluses and minuses of lives basked permanently in the presence of gods. Elvis signs some black-and-white glossies, and everybody, including the movie’s audience, gets to go home.

That “Elvis & Nixon” proceeds generally conflict-free is an inconvenient fact that, in the annals of art-house esoterica, isn’t particularly important, but in a big-budget studio picture can result in an awfully pointless evening at the movies. Despite its three writers, the film just isn’t funny enough to sustain its nonstarter of a premise, and its awkward stabs at contemporary relevance (“This thing with the Iraqis and the Syrians will go away in a couple weeks,” Nixon advises his staff) feel like just that.

Mostly, it’s a museum piece, a moving exhibition of meretricious interiors, loud clothing, shag haircuts, copious sideburns and period funk tunes. As for the rest of the music, Edward Shearmur’s score is as anonymous as Johnson’s direction—the kind of innocuous public-domain muzak that a call center might use as its on-hold music. It’s an appropriate metaphor for the entirety of “Elvis & Nixon:” You spend the whole movie waiting for something to happen.

“Elvis & Nixon” is playing at Cinemark Palace and Regal Shadowood in Boca Raton, Muvico Parisian in West Palm Beach, the Classic Gateway Theatre in Fort Lauderdale, and Regal South Beach in Miami Beach.