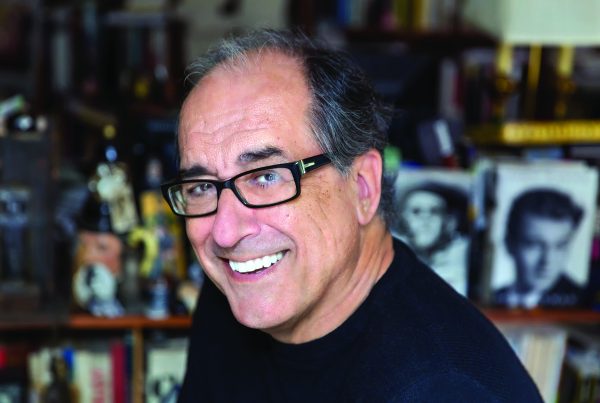

Like many hipsters in the mid-1970s, Bobby Grossman had the foresight to take his art degree from the Rhode Island School of Design and move to New York. This was back when New York wasNew York;it was gritty and full of twitchy energy, anchored by an unrivaled nightlife.

Grossman assumed he would continue his passion for illustrations and seek employment at a magazine. Instead, he found himself hooked on the city’s burgeoning punk scene. He was already friends with Chris Frantz, Tina Weymouth and David Byrne, three pals from RISD who had formed Talking Heads and were the talk of the New York underground. It wasn’t long before Grossman was taking his point-and-shoot Polaroid to CBGB’s, Max’s Kansas City and other influential hot spots, shooting his new friends before, after and during concerts; Blondie, David Bowie, Iggy Pop and the Ramones were among his subjects. He also ingratiated himself with Andy Warhol, becoming a top photographer of the artist’s Factory.

Images by the Boynton Beach-based artist have appeared in nationally released documentaries about William S. Burroughs and Jean-Michel Basquiat, in the pages ofVogueand on the airwaves of MTV. Interest in his photographs haven’t waned since he moved to Palm Beach County eight years ago. He has exhibited at the Sundy House in Delray Beach, and his retrospective “Low Fidelity” was a hit at Vertu Fine Art at Boca Center earlier this year.

“As time goes on, people seem to have more have more interest in collecting them,” says Grossman, 58. “I’m planning that it will see me through my retirement.”

1. Do you feel like you were at the right place at the right time?

I always say I came to the party a little late. The scene had started in the early ’70s with the New York Dolls. But I guess I was there at the right time … people from all over the world were coming to New York to see what was going on. Towards the end it had gotten so commercial that I had had enough.

2. Did these musicians and artists ever have a problem with you documenting them so closely?

I tried to not be obtrusive. I made a point of being background. At times, I missed out on things, being that way, but I figured being less aggressive was better than being in someone’s face.

3. Did you witness anything dramatic between band members?

There would be day-to-day stuff that would happen … you’d read in the paper the next day that one of the Ramones got beat up, or the Dead Boys’ roadie got stabbed, and it would be in the front page of theNew York Post. It was life in the New York in the ’70s.

4. Why do you think there is still such a clamoring for the short-lived punk/new wave scene that you documented?

Because everybody is more interested in a generation other than their own. It was like that for me with the ’60s bands. As time passes, this becomes more history. For instance, young art students now admire Jean-Michel Basquiat; as time goes on he seems to be more and more popular.

5. What do you think of punk music today?

It depends what it is. I sometimes will impulsively give something a listen, thinking that it’s something I’ll be interested in; most of the time, I’m disappointed and it doesn’t hold my interest. Each generation has its own music.

To read more, pick up a copy of our September/October issue.