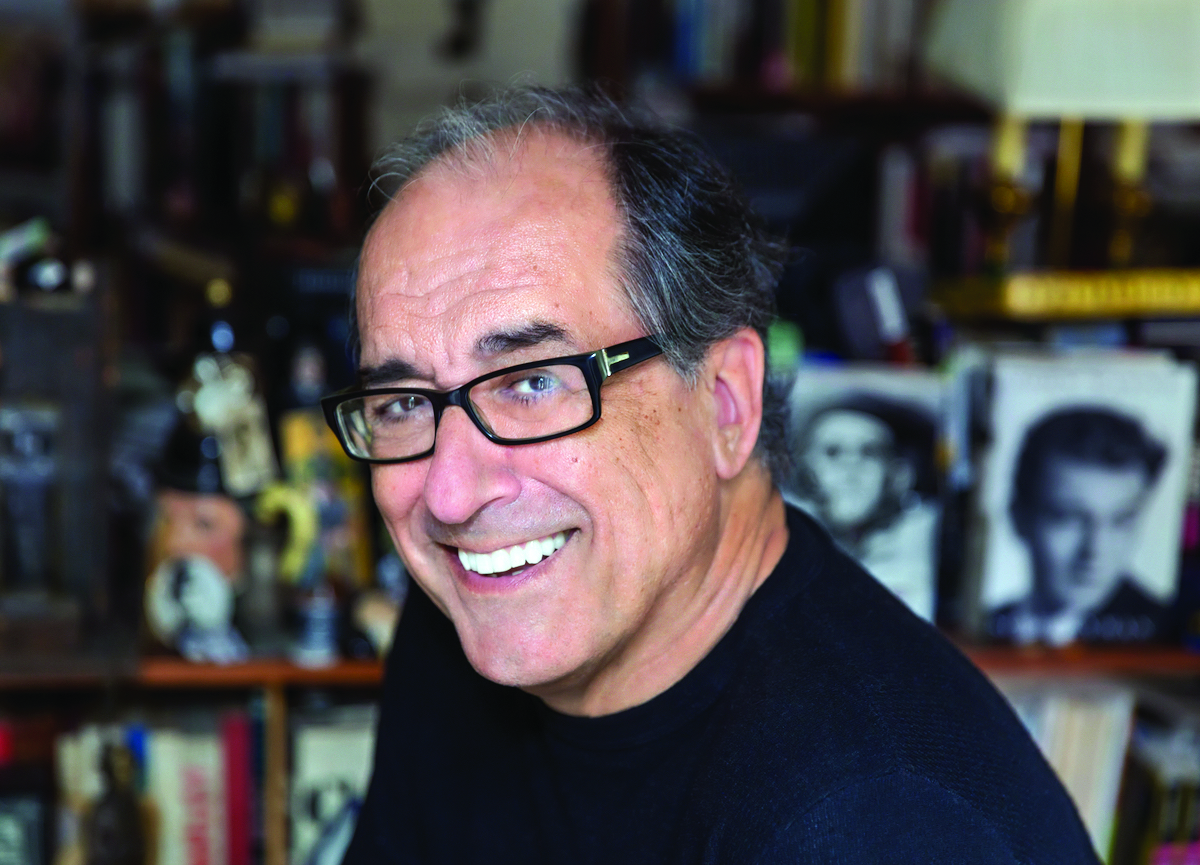

For the February issue of Boca magazine, I spoke with Scott Eyman, a renowned film historian based in West Palm Beach and the author of 17 books on the stars, producers and directors who built the movies into the dominant entertainment form of the 20th century.

Our conversation focused on Eyman’s latest book, “Joan Crawford: A Woman’s Face,” which charts the famed actress’ rise from a penurious childhood to one of Hollywood’s most charismatic and versatile performers across a career that spanned more than 45 years. We continue the conversation in this exclusive Web Extra.

On the studio system in which Crawford rose to fame: Most actors of the period I write about, the 20s through the 50s, did not come from money. Most of them were lower middle-class. It describes Crawford; Bette Davis became lower middle class; Barbara Stanwyck. Few actually did come from comfortable circumstances—Irene Dunn, Gene Tierney. But there weren’t a lot of actresses like that. Girls born from wealthier or well-off families weren’t encouraged to go into the theatre. It wasn’t a reputable profession. It was more open to people from middle and lower middle-class and poor people, because they were looking for the next rung up, and they didn’t care about social position. They just wanted a place of some financial security, and actors could make a lot of money. They could also starve to death, but they were used to starving to death, most of them. So this was a shot worth taking.

The plus of it is you’re getting paid 40 weeks a year, with 12 weeks off at the studio’s disposition. That’s more than most actors make if they’re in the theatre. If you’re 35, and were doing time in the sticks in your 20s, that looks real good. And the money was good. Crawford’s making $500 a week a couple of years after she starts in the movies, and that’s more than a middle-class lifestyle, even in L.A., because a nice house in Brentwood cost 12 grand. It was an upscale environment for someone like Crawford, who came from Bumf**k, Kansas.

The downside is that you were a bond slave. You basically had zip power. If it wasn’t contractual, you didn’t have power. As you gained success, you gained a little more leverage, but you never had 51% leverage under the studio system. The most you could hope for was 49%. Because ultimately, you had to do the scripts they wanted you to do, or they’d lay you off or suspend you, and suddenly the money stops.

Which is why Cagney left Warner Bros., why Bogart hated Warner Bros., but they all stayed there for 15 years, because they ultimately became stars there. And I think after a while, you figure, well, they must know something of what they’re doing, because when I came here, I was making $100 a week, and now I’m making $3,000 a week, so maybe I should shut up.

On Crawford’s peak period: I think her peak period is 25 years, from the early ‘30s through “Autumn Leaves” (1956). … Now there are dips in there; in the late ‘30s she’s floundering, but “The Women” lifts her up. Basically she says, I can’t do this anymore. She had a very good antenna. Suddenly she’s not getting the best scripts—Greer Garson and Vivien Leigh are now getting the best scripts. Crawford isn’t really right for “Strange Harvest” or “Mrs. Miniver.” They’re not developing scripts of an equivalent quality for Crawford. They’re developing them for Garson and other people. So she can sense the ground shifting underneath her. And they’re giving her B movie scripts. She was working with George Cukor; at the end, she was working for Richard Thorpe. Even on the lot, they knew there was a huge gap between Cukor and Thorpe.

So she makes the hard decision: “I’m getting out of here.” She didn’t have a gig at that point. She opts out of MGM in favor of unemployment. A month or two later, she signs with Warners, but nothing happens for a year, because they’re sending her crappy scripts, and she’s turning them down.

Films got more expensive at Warner Bros. But then, because “Mildred Pierce” is such a hit, they start spending real money, on “Humoresque” and the second “Possessed.” Those are very expensive pictures. They’re really chinchilla and mink—big sets, lots of extras, throbbing romantic music, Isaac Stern dubbing John Garfield on the violin. They were spending lots of money that they didn’t actually need to spend. If you look at “Humoresque,” they made it a big, lavish soap opera. It didn’t have to be lavish. They could have just shot the story without all the classical music interludes. It could have just been a story about a young, hungry kid who shacks up with a rich, dissolute alcoholic society broad and uses her and then dumps her. You didn’t have to have all the lush, plush stuff that surrounds the setting.

On Crawford’s late-career decline: In the ‘60s, the studios held her with stories, material and treatments that TV couldn’t get close to—violence, sex—because you couldn’t do that stuff on television. So the movie industry changed. And she basically doesn’t work for three years, after “The Best of Everything” in 1959. She’s working for Pepsi-Cola full time, but that was something she could throw herself into.

Then comes “Whatever Happened the Baby Jane?”, and suddenly she could work again. But the work she gets is other movies like “Baby Jane,” except they’re not as good. They’re exploitation pictures. “Baby Jane” is an exploitation picture-plus. Yes, it plays off the celebrity of formerly huge box office movie stars in shabby circumstances, and there’s a certain semi-erotic thrill in that, and there’s a lot of “Sunset Blvd.” in that story. But both Davis and Crawford hadn’t been seen in quality material for a long time. So it was almost a reintroduction for the audience that loved them and remembered them, and was a great comeback for the people that hadn’t known them, which was considerable at that time.

But Crawford started working for William Castle, because Castle gave her a percentage. It gave her a lot of money. But if you’re going to work for Castle, you’re following in the glorious footsteps of Vincent Price. It’s low-rent stuff, but that’s where the market had moved. That’s where her offers were coming from.

The market for that had moved to episodic television. And she did some good stuff on TV—the “Night Gallery” episode that Spielberg directed. But TV’s forgotten. Once it runs, you can dig this stuff up on YouTube, but unless you’re someone like me, or some crazed movie nut in New York City, that’s not stuff people look up. They want to look at a movie movie, not something somebody did on television for five days. She was relegated to semi-campy horror pictures.

On the continued appeal of the studio system as a focus of his books: It’s about the content. It’s the industrial component. It was a closed system that worked. It was like the American automobile system. It was controlled by the guys who founded the industry in the 1910s and 1920s, and then controlled it for 30 or 40 years. Warner was there for 50. So they had an absolute comprehensive overview of how the business should run. It was hard to get into; it was hard to get out of. Once you were in, you were in. And it made a certain sense, until it didn’t.

And what changed the equation was television, gradually, in the 1950s. And then they had to start changing. They had to cope when actors became independent. They could not control the lives of the actors or writers or directors anymore in the way that they had. So the idea of a closed system, where you’re in control at every stage of the making of a movie, from the property to the writing of the script to the casting to the production to how it’s advertised in the theaters, is all followed through in the same system. And I find that fascinating. It was financially coherent; it redounded to the benefit of both the bosses and employees. The bosses made big money, the employees made good money, and they had job security. So everybody was sort of happy, but at the same time sort of unhappy, because that’s the human condition. Even though they’re making three or four thousand a week, they can bitch about this, that or the other thing. But it was like people griping about the formula of the assembly line.

But after all that fades away, in the ‘60s, as the old boys die off, then you get this flurry of creativity in the movies of the ‘70s—Hal Ashby and Polanski and Coppola and Arthur Penn, making wonderful movies. But then comes the third stage, old age and senility, which is where we’re at now, where people like Mark Wahlberg can have 40-year careers, with no visible display of talent.

Because there are so many different levels of work. If you can’t sell tickets to a movie movie anymore, you can always find some piece of shit from Netflix or Amazon, about a hitman in Yugoslavia. It’s a group grope at this point, and there’s no continuity to it. There’s no theory of entertainment behind it. It’s just, will anybody tune in on this?

And the theater business is dying. I don’t see how you can keep a theater open when there’s only 10 weeks a year when people will actually go see a movie. There are three or four movies a year people will pay to see, but why pay to see it when it’s going to be on streaming in six or eight weeks? There’s no incentive to see a movie in a theater.

Centrifugal force is spinning people onto the periphery, and now there’s no center whatever. To write about today would be impossible, because there’s no narrative in the movie business now. It’s just catch as catch can—this next, next week, next month. But in the period I’m writing about, there was a coherent narrative. There was a coherent system. So you can follow it and see, both through the documentation that’s available and you could also reverse-engineer how they were thinking by what they were making, and why.

It’s just more practical for a historian. You don’t write history on the spot; you write history in retrospect.

This Web Extra is from the February 2026 issue of Boca magazine. For more like this, click here to subscribe to the magazine.